The rubbing of inscriptions on bronze and stone artifacts has been a simple but effective way to duplicate information for more than two millenniums in China, and a new exhibition at the Shanghai Museum is now showing visitors just how important this craft has been.

Advancing With the Times: The Technique of Rubbing features 37 sets of cultural relics, as well as bronze and stone artifacts. The exhibition will run until Oct 8.

The rubbing of inscriptions was practiced in different civilizations but it was only in China where it evolved from a practical skill for duplicating information into a genre of art in its own right, says Li Kongrong, the curator of the exhibition. Li is also the third generation inheritor of the rubbing technique at the Shanghai Museum.

The objects suitable for rubbing range from cliff-carved statues to oracle bones and seals, Chu Xiaobo, director of the Shanghai Museum, said at the opening ceremony of the exhibition on July 6.

To make a rubbing, the craftsman first overlays a bronze or stone artifact with paper before performing ink-rubbing to precisely copy onto paper the features of the artifact, including its shape, patterns and inscriptions.

Today, rubbing can be found on the list of the national intangible cultural heritages, and is widely used in such fields as archaeology, cultural heritage studies and museology.

The technique is inextricably linked to the invention and application of ink and paper and the demand for higher production efficiency. Although it is difficult to exactly pinpoint when rubbing first appeared, Li says that historical research suggests it started no later than the 5th century.

Most of the exhibits are from the Shanghai Museum's collection. Those that aren't include a photocopy of Rubbing of the Inscription on the Hot Spring, which is owned by the Bibliotheque Nationale de France. The original text was composed and written by Emperor Taizong (599-649) of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) before it was inscribed in stone in 648.

The original stone piece is long lost but the rubbing was discovered in 1900 in a cave dedicated to preserving Buddhist sutra in Dunhuang of Gansu province.

Today, the rubbing is recognized as an important artifact for the study of calligraphy in China. The ancient rubbing suggests that the technique in China was already mature by the 7th century.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) witnessed the growing appeal of epigraphy, when the literati and scholars showed great enthusiasm studying bronze and stone artifacts. The interest prompted advancements in the craftsmanship of rubbing and the application of the technique to more types of artifacts. The invention of new skills such as composite rubbing transcended the boundary of the traditional technique and made possible the impression of three-dimensional artifacts on surfaces.

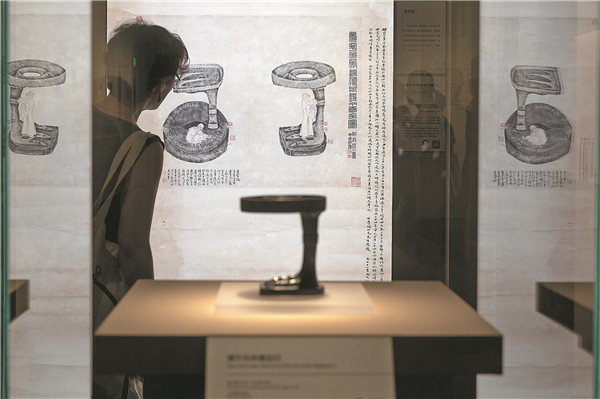

One of the exhibits, Scraping the Patina Off the Lamp illustrates the combination of rubbing technique and the art of painting in this period. The artwork features the rubbing of a bronze goose foot lamp dating back to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) by a monk named Liuzhou (1791-1858) and a painting by Chen Geng.

Measuring 87 centimeters long and 51.5 cm wide, this artwork depicts two versions of rubbing for the lamp side by side, one with the goose foot facing up and the other in an upright position.

Chen depicted the monk as a small figure scraping the patina off the lamp.

If you go

Advancing With the Times: The Technique of Rubbing

July 7-Oct 8, 9 am-5 pm, Tuesday-Sunday.

4F, third Exhibition Hall, Shanghai Museum, 201 Renmin Avenue, Huangpu district, Shanghai.

021-6372-3500.