During the event, which took place in a scenic spot named Lanting (Orchid Pavilion) in what is now the city of Shaoxing, in Zhejiang province, all 42 participants were seated alongside a winding brook, whose halting flow carried cups of rice wine downstream. Whenever a cup came to a hesitant stop, the nearest person was required to imbibe its contents before coming up with a poem.

Wang, regarded by many of his successors as the greatest Chinese calligrapher of all time, wrote the preface for the poetry collection, a literary and calligraphic masterpiece whose fame grew to such an extent that Li Shimin, a 7th-century emperor of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), was believed to have sought it out and taken it with him into his own burial ground.

Fortunately for modern-day art lovers, copies of the original writing by other hugely talented calligraphers were made before it disappeared.

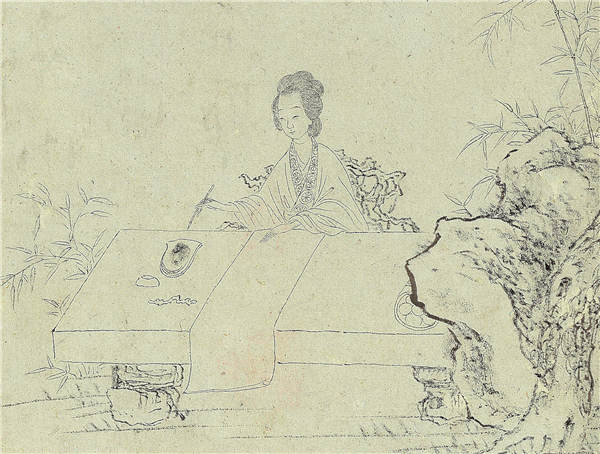

Then there are the images-numerous paintings made by later generations to help imagine the event, two of which are now on view in the New York exhibition.

"It's important to remember that calligraphy was not born as a blue-blooded form of art," Wang of the Palace Museum said. "People skilled with the use of a brush were once relegated to the role of scribe, with the task of putting down what their superiors had to say, often in official announcements or documents.

"Wang Xizhi was undoubtedly a leading figure in elevating calligraphy to a level worthy of the lifelong trying of a scholar-gentleman. That preface he wrote sealed the deal."

Another, equally far-reaching impact the gathering had was on literati painting, Wang said.

"Writings came first, followed by pictures, since it is words that inform a picture and imbue it with meaning. This is something that is distinctly Chinese, something that sets the tradition of Chinese literati painting apart from all the other great painting traditions of the world."

Wang once studied Chinese art history at Beijing Normal University. Among his teachers was the renowned contemporary calligrapher Qi Gong (1912-2005), a descendant of the ruling Aisin-Gioro family of Qing (1644-1911), China's last feudal dynasty.

"One story he was fond of telling was of when he, as a young man, took his own paintings to a senior family member and painting master for advice. The old gentleman asked a single question before agreeing to open the scroll: 'Does it have a poem?'," Wang said.

"What he meant was that a painting not made by a literary-minded man was decidedly second-rate. In other words, throughout its history, a piece of literati painting was often judged not so much on the merits of its brushstrokes as on its import."

Although literati painting came into being only in the eighth and ninth centuries-before that the scene was dominated by professional painters who were skilled artisans with little formal education-it was able to draw from the immense cultural and spiritual legacies of the previous centuries, to which both Wang Xizhi and Tao Yuanming were contributors.

Having died in 361, four years before Tao was born, Wang Xizhi was spared the demise of the Eastern Jin Dynasty in 420. This is particularly important because the calligrapher came from the powerful Wang family that helped shape the dynasty's politics.