With the end of the dynasty, China descended further into political chaos and disintegration. Yet this highly volatile period between the third and sixth century was also marked by flourishing art and literature, which some believe may have been partly fueled by the inner struggle of the disenchanted literati class whose members chose to be recluses in unprecedented numbers.

Proving to be immense inspirations, these men and their words found their way into numerous paintings and poetry by later generations. One of them, by the 19th-century painter Liu Yanchong and featuring seven highly adulated writer-hermits from the third century, can be seen at the exhibition.

Known as the "seven sages of the bamboo grove", these men joined Tao in the pantheons of Chinese hermits, due as much to their mutually nurturing friendship as to their literary genius. In what is now Xiuwu county in Henan province, they enjoyed regular get-togethers in the bamboo grove, where they famously let wine and creativity flow freely.

"A hermit is not necessarily a loner," Scheier-Dolberg said. "Communion is not viewed as the opposite of reclusion in premodern China. Rather, the act of separating oneself from society often meant opting out of relationships of necessity and into those with the like-minded, for mutual enjoyment."

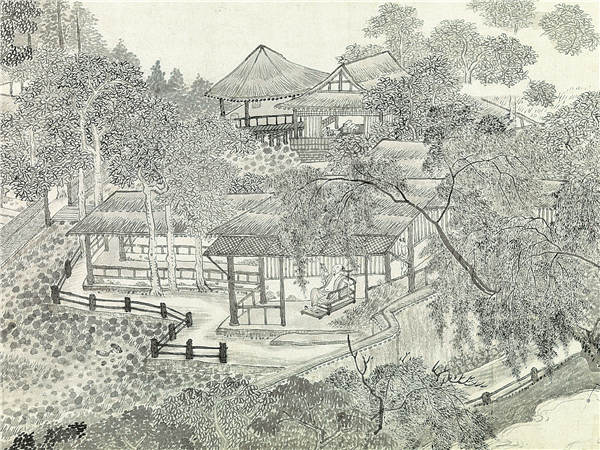

Scheier-Dolberg pointed to paintings that show small gatherings, taking place either against a natural background or in what he called carefully curated garden spaces on one's home estate, complete with "cultivated trees and fantastic rocks", all strategically placed to evoke a natural sanctuary and stimulate contemplation.

According to Wang, the limited number of people in those paintings, and the way they were presented-either as pages in booksized painting albums or as long, horizontal scrolls a viewer is expected to open gradually in hand, speaks for the gathering as part of a minority culture.

"The depiction of these events, as the events themselves, were never meant for a crowd," Wang said, pointing to painted home-dividing screens, often seen in ancient Chinese households for the well-off, as examples of popular art.

"The albums and hand scrolls were shared among a knowing audience who saw themselves or their alter egos in them, and were capable of reading between the brushstrokes."

These get-togethers were called elegant gatherings, a term that may sound slightly pretentious. Yet going by what Wang says, the participants had every reason to feel good about themselves.

"Of course they drank wine, played chess, burned incense, spent time looking at some precious old paintings, but the core part of an elegant gathering was composing poetry. Guests were required to write poems based on game rules, to use a specific word or to let the poems rhyme on a certain sound, for example. Failure to do so would probably make one appear less elegant than one had wished to be."

As daunting as that possibility appeared, it turns out that ancient China produced its own bumper crop of talents who reveled in the challenge. Some joined Wang Xizhi, a fourth-century calligrapher and writer of prose, in an elegant gathering he organized, one that has been immortalized by the resulting collection of poems.