Shan’s opinion was echoed by Ma Guoxin, an academician at the Chinese Academy of Engineering. Ma has designed the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Tian’anmen Square, the National Olympic Sports Center and Terminal 2 of the Beijing Capital International Airport.

Ma cited the Imperial Hotel of Tokyo designed by American master architect Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1920s as an example. In his creation, Wright merged Western design principles with a fascination with Japanese culture, and it was used as a shelter for thousands of people during the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake while many buildings around it were ruined. However, a controversial decision in 1967 led to its demolition.

In recent years, UNESCO has inscribed many architectural works designed by modernist masters such as Wright, Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and Mies Van Der Rohe on the World Heritage List, on which nearly one-eighth are 20th-century heritage sites.

However, none of China’s 20th-century heritage sites have made the list.

Experts at the event attributed the fact largely to inadequate attention to 20th-century buildings in China, as they are often deemed as still young. It was not until the start of the 21st century that experts and heritage protection authorities started to realize their importance.

In 1999, the International Union of Architects was held in Beijing, bringing together more than 30,000 scholars and experts.

The congress adopted the Beijing Charter, drafted by renowned Chinese architect Wu Liangyong. The charter advocated that, only by summarizing the laws of architectural creations in the 20th century and examining their value with the perspective of heritage, can architects design better works facing the new century.

In 2008, China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration issued a notice to strengthen the protection of 20th-century heritage to keep abreast of an international trend in protecting heritage left from the last century.

In 2014, the Chinese Cultural Relics Society established the committee on 20th-century architectural heritage, which is the country’s largest academic body for the scholarship of 20th-century architectural heritage. It consists of some 110 members, including academicians, veteran architects and archaeologists.

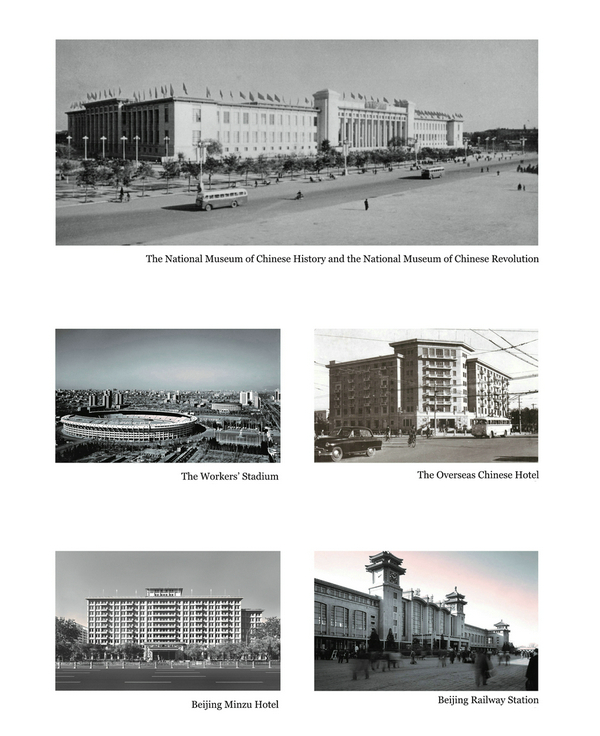

Since 2016, the committee has carried out comprehensive surveys around the country and has been publishing a list of 100 architectural sites every year. So far, it has published seven lists, a total of 697 architectural sites built in the last century, including factories, railroads and university campuses.

Those old buildings embody the ideals and aspirations of the 20th-century people. Buildings with value, including historical, scientific, cultural or emotional value, should be preserved because they are part of the historical chain, Shan remarked.

Experts also remarked the book’s publication can help raise public awareness of 20th-century architectural heritage, which is crucial for encouraging public participation in protecting heritage sites.

Shan hailed the practice of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) government, which, in 2008, initiated the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme.

Under the scheme, non-profit organizations can submit proposals to use those government-owned old buildings, including hospitals, courts and staff quarters, to provide services or businesses to the local community.

As of 2018, eight properties have been opened in their new functions. New uses include a museum, a marketplace, a creative arts psychological therapy center and a facility to train guide dogs for the blind.

“It’s a sustainable way for the Hong Kong government to incorporate heritage protection into community life,” Shan said.

Zhang Song, an architecture professor at Shanghai’s Tongji University and co-author of the book, argued that China should learn from Europe’s practice because it’s a world forerunner in protecting Modernist heritage since the 1980s through conventions and treaties.