Australian Nobel Prize laureate Barry Marshall's China story begins with a child and some sugar cane.

A physician and professor at the University of Western Australia, he first visited China in the 1990s. He traveled to Guilin in the southwestern Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, a popular tourist destination recommended by a Chinese scientist and well-known for its karst landscapes.

"Of course, Guilin must be one of the top tourist destinations in the world," he says.

Back then, Chinese people in non-urbanized areas hadn't seen many foreign visitors, and almost nobody in such areas spoke English.

Marshall recalls his Chinese friend asking him to take care of his son for a moment while he went to get his car. The boy suddenly started crying and attracted the attention of a number of local people. Finally, an old lady managed to appease the child with sugar cane.

"So it was very stressful for me. Because all the people that gathered were like, 'how've you got that child and you don't even speak Chinese?'" he remembers, smiling. "I was determined to learn Mandarin after that."

Now the little boy, whose father Marshall is still in contact with, has grown up, while the professor's interest in Chinese culture is also growing.

With a disciplined approach, he has been attending Chinese class, at least once a week, to learn the Chinese language, tai chi and Chinese calligraphy.

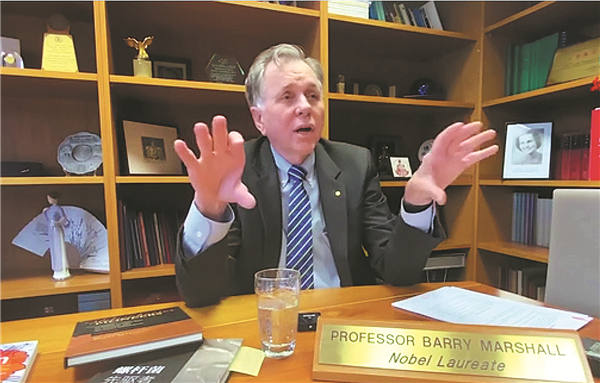

In 2005, Marshall was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine jointly with Dr Robin Warren for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.

"I really got involved with China after the Nobel Prize, going more often with the university," he says.

To date, he has been to China numerous times, and can talk with knowledge about the various places he's visited, such as Beijing, Xi'an, Chengdu, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Zhengzhou, among others.

Throughout the years, he has been impressed by the pace of China's growth, as well as the enthusiasm of Chinese universities and institutions for international scientific research.

"After I won the Nobel Prize, I traveled with the vice-chancellor of the University of Western Australia to Beijing. That was a very interesting trip because that was one year before the Beijing Olympics … There were lots of new scientific activities and innovations in China at that time," he says.

"I think everybody was very optimistic and excited in those years just before the Olympics, even up to, I think, 2010, there was the Shanghai expo. I went to that and I could see that things were being done in China."

Dec 21 marked 50 years since the Australian government, under then-prime minister Gough Whitlam, established diplomatic ties with China.

This paved the way for China to become one of the first countries to sign a science and technology treaty with Australia in 1980 — the 30th anniversary of which was celebrated at the World Expo 2010 Shanghai attended by Marshall.

According to the Australia-China Relations Institute, the relationship has delivered a "boom" in scientific knowledge.

A report published by the institute in 2020 found that the number of Australian scientific publications involving a researcher from a Chinese institution increased by 13.1 percent in 2019, making China Australia's leading partner for producing scientific publications.

Collaborations with China accounted for 16.2 percent of Australia's total publications, up from 3.1 percent in 2005.

Marshall says he was encouraged by the scientific development in China.

" (There are) a lot of world-class science activities in China and good collaboration internationally," he says, and, "lots of advances in China, which I could bring to Australia."

In 2015, Marshall was awarded the Friendship Award by the Chinese government, the highest award to commend foreign experts who have made outstanding contributions to China's modernization drive.

Now Marshall is engaged in a project with Shenzhen University in South China's booming Guangdong province, having established the Marshall Laboratory for Biomedical Engineering, which studies and performs research on the engineering aspects of biosystems to create new procedures, technologies and devices to improve health and quality of life.

Besides the ongoing research projects, the two sides also set up a bio-tech startup company to help actualize the laboratory's inventions.

High-tech engineering methods of disease diagnosis and treatment are currently in development, with one of the many goals being to develop a more efficient and accurate way to diagnose Helicobacter pylori, a major pathogenic factor of stomach cancer.

Despite relations between the two countries having their ups and downs, Marshall says that science exchange remains healthy.

"I think there's lots of good value scientifically in having an exchange with China. And I've had a few engineers from China doing PhDs in my lab this month," he says.

"We still want to publish, we still want to collaborate … I see these activities, gadgets and computerization and virtual technology and all that kind of stuff. And there are some good ideas there that we could incorporate in Australia."

Looking ahead, Marshall says he would like to visit China again for a boat trip. He used to live in a hotel in Shanghai, where he could see boats going up and down the river.

"It was wonderful to just visit with my family and there are still a lot of activities that I'd like to do in China," he says.