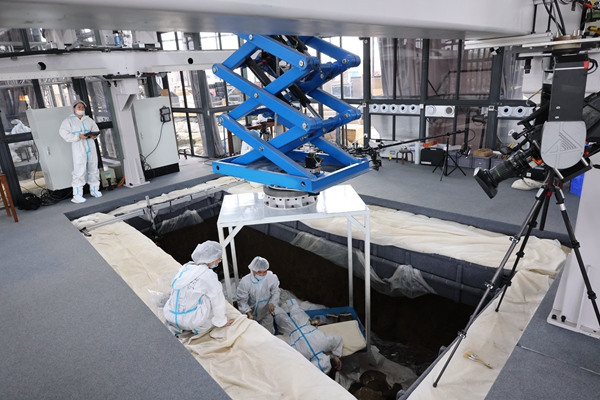

A structure provides an extra protection for these capsules in case of bad weather. Seen from outside, the excavation site looks like a high-speed train station.

Also, for the first time in China, laboratories have been set up at the site to enable real-time conservation of unearthed relics and the analysis of findings.

"It's like an emergency hospital for the relics," says Wang Chong, a cultural relic conservator working on the site.

"They are comprehensively tested and we decide to which department they should go... These technologies have been used in our work for some time, but we never gathered all the facilities on the front line of archaeology before."

Eight high-definition web cameras have been placed on-site. Chen says they are connected with other experts via the cloud in case further consultation is needed.

In 1986, the focus was on the artifacts found, but new developments in archaeology have now made it possible to take care of the soil dug up during the excavation of the pits.

"The soil is also considered as a cultural relic now," says Ran Honglin, a leading archaeologist at the ongoing excavation.

"By categorizing it in detail, we want to collect and record information as comprehensively as possible like building up a library. Researchers in our future generations can also benefit from our work."

Some findings in the soil have surfaced despite the relatively short time. For example, fibroin was discovered within a tiny soil sample, and a fabric pattern appeared in the lens of a microscope, indicating the use of silk in sacrifices.

Finding the time period of relics has been a question for researchers at the Sanxingdui ruins as radiocarbon dating results of artifacts unearthed from No 1 and 2 pits varied greatly in the past. Nevertheless, compared with purely relying on the artifacts, the soil provides a larger and more reliable sample to be studied.

A report by China Central Television on Tuesday said, according to the newest radiocarbon dating, based on samples of carbon dust collected from the soil of No 4 pit, it might date back to between 1199 and 1017 BC.

"Do all the six pits belong to the same period? Dating results will help us to understand their function and significance better," says Sun Hua, a professor at Peking University.

The development of new technology will help. For example, how to preserve more than 100 ivory tusks that have been found during the ongoing excavation.

"Conservation of ivory is a problem commonly faced by archaeologists worldwide," says Wang Yi, director of Sichuan Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration. "We're exploring, and a cautious attitude is needed before adopting new methods."