As Lin and Liang surveyed the wooden temple in 1937, her keen eye picked out faint inscriptions beneath the main beam, providing crucial evidence of the building's age, her son Liang Congjie wrote in his article, Reminiscing About My Mother Lin Huiyin, in 1987.

Wang Nan, senior engineer at the Palace Museum in Beijing and one of the curators of the exhibitions, says recognition of Lin's discovery represented the first time that she had been allowed to stand on the same academic and intellectual pedestal as her husband.

"Liang is often regarded as the father of modern Chinese architecture, and a common misconception is that he sparked in her an interest in architecture. With the discovery of more records, and Lin's manuscripts, her outstanding contribution to architectural history becomes evident."

In a paper published last year in the journal Modern Science, researcher Meng Zhaoyuan analyzed media coverage of Lin over the past century, in which she is often portrayed as a member of the literati and an activist, overlooking her identity as an architectural scholar. In fact in newspaper reports over the decades, mentions of her beauty and romantic life very much eclipse other things.

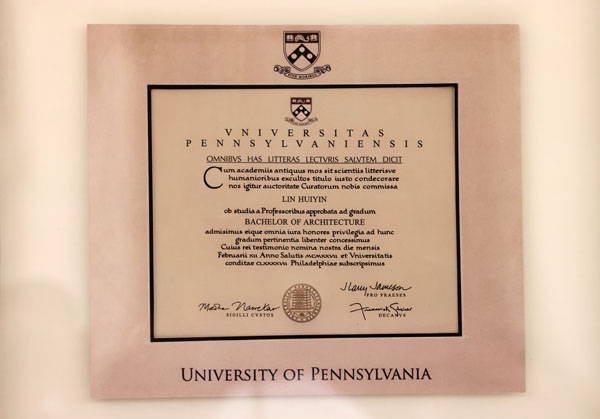

On June 10, the 120th anniversary of Lin's birth, the architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania, which is now under the Stuart Weitzman School of Design, put everything in its correct perspective. At its annual graduation ceremony a month earlier, it awarded Lin, who died in 1955, a Bachelor of Architecture degree in recognition of her pioneering contributions to Chinese architecture.

"All the men from China received full scholarships and Lin got half of one. She was the only woman and the only student who wasn't allowed to get an architecture degree," Dean Frederick Steiner said.

"My mother had a strong sense of freedom," Liang Congjie wrote in his article. "Even though she was a university teacher, published articles and was famous, she was stripped of her own identity and simply regarded as Liang Sicheng's wife."