"It is the time for cherries and bamboo shoots in Jiangnan/the moist greens are refreshing/As the rain falls, peach blossoms arrive with the rising water/the crops sprout as spring hurries into the season."

The poem, from 16th-century painter-calligrapher Wen Peng, was composed to accompany the painting of his friend Qian Gu — both active members of a coterie of literati-artists formed around Wen's father.

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), the old man, had once been recognized as a young genius, before spending four years in Beijing, capital of China during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), to pursue what seemed to be a promising career that he had long deserved. What happened at the end of that stint was that he packed up and went back home to the city of Suzhou, located in Jiangnan — the southern part of the Yangtze River Delta.

Over the ensuing 32 years, the senior Wen turned himself into something of a cult figure. On top of his talent was the public perception of him as a man of high moral standards who disavowed the seedy side of politics in favor of a secluded existence in the garden abode he built for himself.

Yet one thing was unignorable: Wen Zhengming's self-imposed exile, as those orbiting around him might wish to call it, was lived out not in sheer harshness, but amid the many enjoyable things that Jiangnan had to offer, including its spring.

"For Wen Zhengming and his followers, the spring of Jiangnan was common subject matter, a shared language which allowed them to interact and bond on paper," says Clarissa von Spee, curator of an ongoing exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art that examines, among other things, the crucial role this region played in China's cultural history.

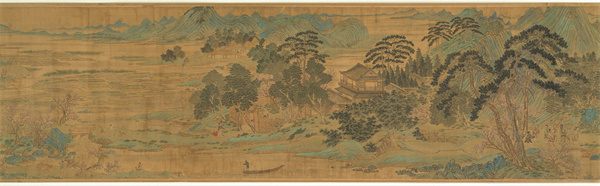

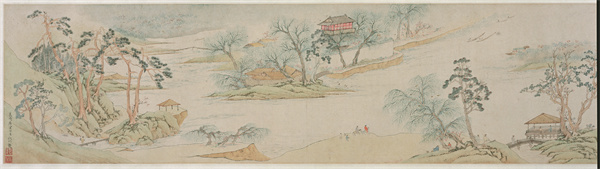

The Wen Peng painting, on view at the exhibition, depicts the classic Jiangnan countryside: paddy fields running along stretches of water, lined by flowering plum trees and dotted with boats and bridges. It shares gallery space with a number of other similarly themed artworks, including one by the much-adulated Wen Zhengming.

"They clearly identified with the land," she says.

A solitary state

In fact, Jiangnan, whose geographical borders had been shifting according to Von Spee, was once a land of exile in the true sense of the word. "During the 3rd century BC, Qu Yuan, a member of the aristocracy from the state of Chu, was banished for disagreeing with what he saw as a corrupt court. In written sources, we find the words 'Jiangnan' for the region he was expelled to — one of the earliest appearances of the term," says Von Spee.

It was during China's Warring States Period (475-221 BC) which, as its name suggests, was marked by territorial wars fought among multiple states. One of them, the state of Qin, eventually crushed all others, and its king, Ying Zheng, subsequently became the first emperor of a unified China, known as Qinshihuang.

While the triumph of Ying Zheng made Jiangnan part of a centralized Chinese dynasty for the first time, the tragedy of Qu Yuan, who drowned himself in utter disillusionment in around 278 BC, infused his land of exile with a nobleness that appealed to generations of Chinese, both morally and aesthetically.