That said, the same creations were aimed at China's domestic market as well, a brightly colored 18th-century porcelain vase that once lit up a Chinese home being graced on its side by two Western women holding a parasol. Its maker used opaque enamels to create shading, giving the images a three-dimensional effect that could also be found in Chinese paintings at the time, thanks in part to the Western missionary-artists who worked in the Qing court.

"The fascination is mutual," Lu says. "But China in the late 18th century was not China in the 14th century."

After banning their ships from the sea and barring foreign ones from coming for more than 400 years, a policy imposed by Ming emperors and reinforced during the Qing Dynasty, China's door was pounded open by British cannonballs during the First Opium War (1840-42). The defeat forced China to open five of its important ports to foreign trade.

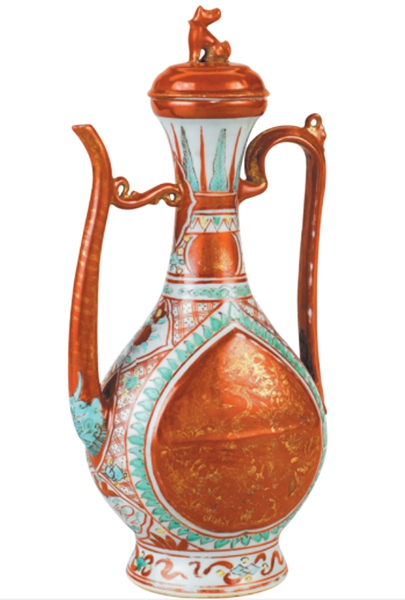

These included Canton (Guangzhou in Guangdong), long the sole point of contact between China and Europe. The city, a center of enamel production and distribution for what is known in the West as Canton enamel, retained its position throughout the 19th century. But other enamel works were to leave the country.

In an exhibition of ancient Chinese cloisonne wares at Bard Graduate Center in New York in 2011, two of the exhibits were an art nouveau jardiniere — a decorative flower box or planter — made around 1870 by the Frenchman James Tissot, and another the artist's inspiration: a similar-looking Ming creation he acquired after it was taken when invading Anglo-French troops sacked the Old Summer Palace in Beijing 10 years earlier.

The current exhibition has two painted-enamel-on-copper-plate dishes intended for the Japanese market. Script on the bottom of the dishes reads: "made in the period of Man'en" — Man'en being a reign of the Japanese emperor Komei (1831-67) during whose rule Japan's first major contact with the United States was made, followed by the country's forced reopening to the West. Komei was succeeded by Emperor Meiji, who oversaw a series of rapid social changes that enabled Japan's transformation from an isolated feudal state to an industrialized power.

For some, the dishes serve as poignant reminders of a China whose luster, that once dazzled and captivated just as the painted enamel did, was about to fade.

Since then China has been transformed, while Chinese cloisonne has been reduced to the category of "crafts", indicating an activity inferior to art-making. What was once hailed for its sophistication is now often viewed as ostentatious and garish, if not banal.

"Tastes change," Lu says. "It's not conducive to our understanding of art history to look at a certain moment merely through the contemporary lens. To do that would be to miss the thrill people at the time must have felt, and the pride they took, at being able to create something that could rival the accomplishments of their ancestors, and hopefully make them proud."