One of his most memorable experiences, he recalls, was detecting a 50-centimeter area of rot at the bottom of a pillar at the city's Yonghegong Lama Temple. "I was so glad I found it in the nick of time," he says.

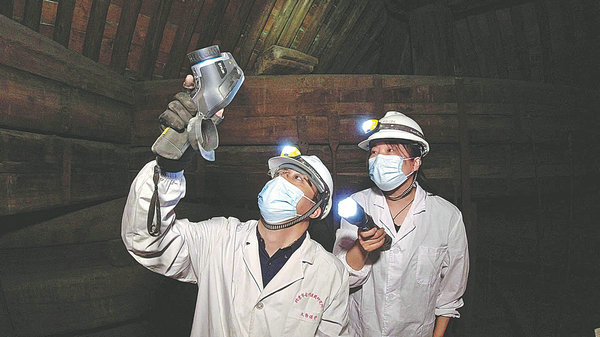

Zhang has been working at an archaeological institute under the auspices of Beijing Cultural Heritage Bureau since graduation. The job has made him a regular at major historical sites across the capital, including the Temple of Heaven and Beihai Park. He is among the handful of protectors of several ancient structures in Beijing, which has more than 3,800 immovable sites boasting a history of over 3,000 years.

Zhang grew up in a neighborhood right next to the Temple of Heaven and is familiar with the grand architecture. "The imperial complex of buildings is indeed magnificent and I get to see it every day," he exclaims.

His knack for experiments and good science scores in senior middle school paved the way for a bachelor's degree in applied chemistry from Shandong University.

"After college, I received job offers from institutes for food quality testing, water analysis and ancient architecture restoration," he says.

Then, the archaeology institute was in charge of restoring the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests at the Temple of Heaven. So, he took the restoration offer and started working on historical stone structures.

Although stones are much sturdier than wood or brick, they are susceptible to weather and erosion. "Sulfur and nitrogen oxides in the air turn into acid when it rains, and acid is bad for stone relics," he says.

Soluble underground salts, too, can cause problems when rainwater seeps into the soil and evaporation coats the stone surfaces with contaminants. "They can accelerate the accumulation of pollutants," he says.

When he first arrived at the site, he had to analyze a stone relic's constituents and the reasons behind its erosion before applying any protective material, including those that strengthen the foundation and shield the structure from the sun's ultraviolet rays.

He later obtained a master's degree in materials science and engineering from Beijing University of Chemical Technology. With time, Zhang became increasingly aware of the importance of testing and diagnosis. "It is like the first step in a hospital, also the most important one, before the course of medication can be determined and administered," he says. He found diagnosis was of great help in choosing protective materials. "If the weathering is serious, you choose materials with a strong potency," he says.