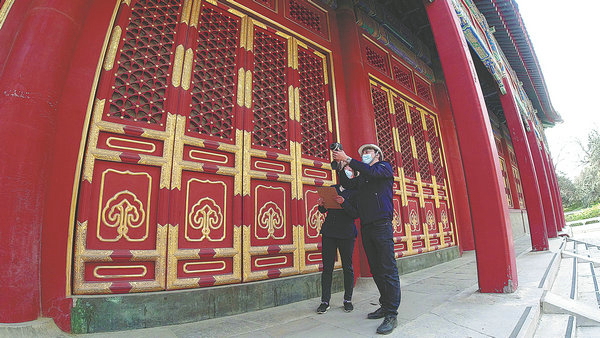

Zhang Tao draws unwanted attention at work every now and then. As he stands in front of historical buildings in Beijing, armed with a sophisticated drilling tool that may look like a weapon to untrained eyes, his seemingly public vandalism is interrupted and questioned by well-intentioned passersby.

"I am actually using a micro-drilling impedance analyzer, which helps me test the health of a building," the 39-year-old restorer explains to concerned onlookers.

"It is like drawing blood (from old structures) for tests. This tool is used abroad to determine the growth of trees," he further clarifies.

Most historical buildings in the city are made of wood, and Zhang and his team are entrusted with their restoration. With the misunderstandings quickly cleared up, Zhang gets down to examining the buildings, determined to preserve what is left, a job he has been dedicated to since 2005.

A few light taps on a pillar with his small hammer and Zhang can diagnose if something's wrong inside the woodwork. He zooms in with the impedance analyzer to detect decay and cavities in the timber. The technology, which is largely used by arborists or tree surgeons, can tell stages of rot and identify hollow areas and cracks.

As the micro-drill bores into the wood, the resistance of the timber changes the needle's rotation and speed. These variations are translated into a graph, which looks a lot like an electrocardiogram, or ECG, printout.

"Maintenance techniques followed by our predecessors are passed on and inherited, and modern technology can help us pinpoint problems in these historical structures," says Zhang. "Many of these buildings are more than 400 years old. They look sturdy on the outside, but may be decaying inside. If they collapse someday, it will be a great loss for all of us."