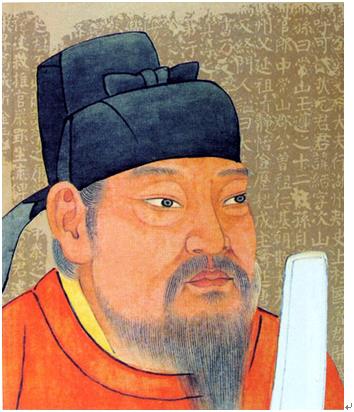

For the Chinese literati, the doctrine of moderation is a key influence in their lives and calligraphy an effective and artful means to express their emotions and thoughts. For the literati, the doctrine of moderation has often been regarded as a code of conduct, which many unconsciously integrated onto their brush tips, giving rise to harmony between art and heart in their works. Celebrated calligrapher Yan Zhenqing (AD 709-784) was one of them.

The core of the doctrine of moderation lies in moderation. The doctrine advocates for finding the best possible solution without going to the extreme. To do so, one must be self-cultivated and understand the objective laws of nature and society. Be that as it may, it is not the same as making compromises or taking the middle way. Instead, it emphasizes "harmony without uniformity" and calls for mutual tolerance without simply "going along with one another". Moderation emphasizes merits of calmness, wisdom, honesty,kindness and intelligence. It also lauds persistence. Such positive and upbeat mindsets have encouraged the Chinese people to be indomitable, resolute, intolerable to evils and fearless against danger.

Yan Zhenqing was a faithful practitioner of the doctrine of moderation both in his work and life. He grew up in a family that valued education and served in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) court. With his noble personality and determination to serve his country, he reversed the downward-tide and prevented the collapse of his court.

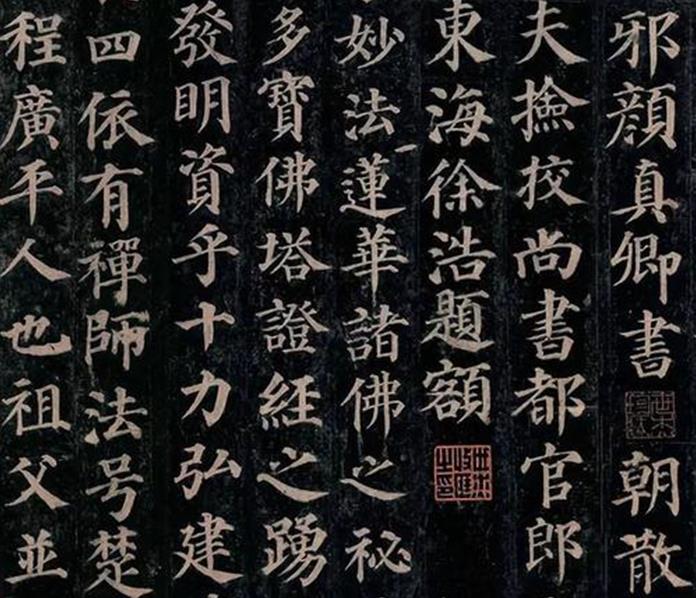

Yan's self-cultivation of moderation trickled down into his calligraphy and art style. Prior to Yan, renowned calligrapher Wang Xizhi's style, which stressed gracefulness and a free and untrammeled form, dominated Chinese calligraphy for hundreds of years. Yan forged himself a new path - a monumental, dignified and powerful style marked by smoothness, stability and masculinity. In the words of Su Shi, the most celebrated scholar-poet of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Yan was the "sole hero who challenged this ancient tradition."

Yan's calligraphy is reflective of his upright, brave and aboveboard life. Simplicity, sincerity, power and generosity run through his brushstrokes, which won him admiration of the distinguished officials, including emperors, as well as later generations.

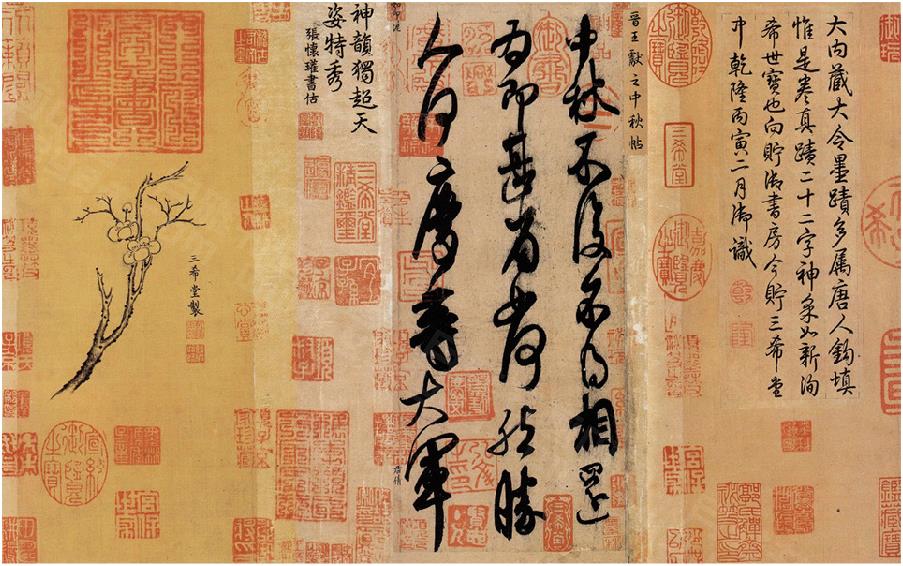

Moderation is also reflected in Yan's sophisticated brushwork in his use of ink and layout, or neutralization. Neutrality is understood as a high degree of unity of contradictions, a balance between yin and yang, and a harmonious integration of the subject and the object. In the context of calligraphy, it alludes to expressions that are mediatory and controlled, capturing the beauty of nature and personality in dots and lines. One such example is running script, in which characters can be big and small, dry and wet, in regular script and in cursive script, even in classic style. All characters in a piece of work are changeable but integrated with the unity of harmony.

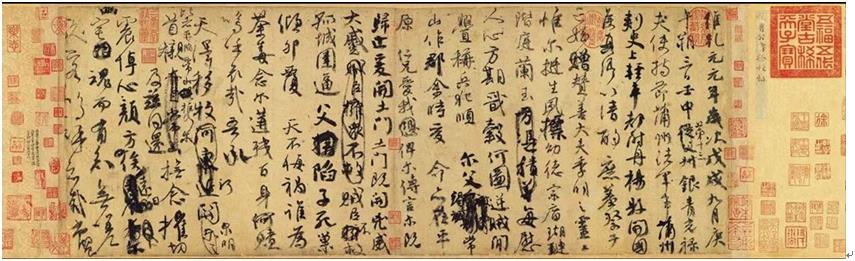

Eulogy for a Nephew (Ji zhi Jiming wen gao) is an example of such neutrality, a piece of work that Yan completed while mourning his nephew Jiming. Hit with emotional turmoil, Yan poured all of his grief and anger out into the work. Most of the characters are oblique, some facing left and others right. Many characters were scribbled and rewritten, making the work seem a little chaotic. Despite a pandemonium of emotions, his brush was still under control, and even the spacing of the characters handled moderately. In whole, the work is well-proportioned, with a rhythm rendered by the change of ink tones and size of characters. Its layout is reasonable, where empty spaces do not appear hollow and useless. At the moment of creation, Yan was not tied by rules of sophisticated calligraphy and let his emotions run free through his brush. Yan's eulogy is another masterpiece in the history of Chinese calligraphy after Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion by Wang Xizhi in AD 353, which is often regarded as the first masterpiece of running script.

The author is a professor at Dalian Minzu University.