Treasure hunt

A cautious and responsible attitude is necessary to complete such a high-profile restoration project of an ancient book-the largest in scale since the establishment of the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books, headquartered at the National Library of China, in 2007.

Regardless of its glory during Qianlong's era, the destiny of Tianlu Linlang was not so glamorous.

In the final years of the Qing Dynasty, some volumes were "lost" when they were taken to be repaired beyond the red walls of the Forbidden City.

After the Qing Dynasty government fell, the last emperor Puyi continued to live in the Forbidden City until 1924. During this time, he also transferred more volumes out of the palace as "gifts bestowed to others".

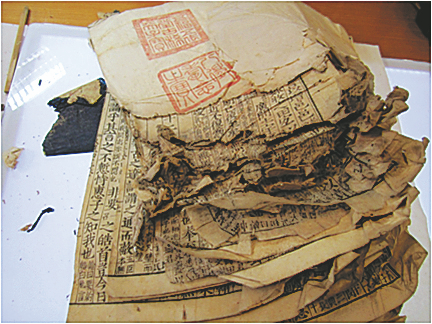

It was later discovered that the last emperor had kept the books in a warehouse, without protective measures, in Changchun, Jilin province, from 1931-45 when he ruled "Manchukuo" in Northeast China, a puppet state controlled by Japan. Some of the books were lost again when his "throne" fell once more.

In the 1930s, about 300 volumes that were still in the Palace Museum were moved first to East China and then to West China when the front line of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) approached Beijing. They were supposed to return to their home after the invaders were defeated, however, in the aftermath of the following civil war, they were taken to Taipei, and have remained there.

Today, 279 volumes of Tianlu Linlang, or 3,500 copies, are housed in the national library. These cultural treasures were transferred from the Palace Museum to the library in the 1950s.

About 40 volumes are housed in Liaoning Provincial Library in Northeast China. Some others are in the hands of individual collectors, but the whereabouts of nearly 60 volumes are still unknown after the past century's upheavals.

"Stories of Tianlu Linlang reflect the change of a nation's fate," says Zhang Zhiqing, deputy director of the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books.

"So the physical restoration bears bigger significance to show a duty toward our culture and history," he says. "It can also provide reference for other conservators of this collection of ancient books."

According to an investigation by the National Library of China in 2013, over half of the Tianlu Linlang books in its collection were at least partially damaged-by water, worm, mold, mice or simply the passing of time-and 10 percent were in critical condition that urgently needed to be repaired.

Preparing for the restoration, librarians at the National Library of China also cataloged these books for the first time.

"Thanks to this project, we can rescue many precious treasures from the Song to Ming dynasties and thus contribute to academic studies," Chen Hongyan, deputy director of ancient books department of the library, says.

Many versions of print books from the Song Dynasty and the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in Tianlu Linlang are incredibly rare.

"Some copies are the only surviving examples of their editions," Chen says. "You cannot exaggerate their value."

Chen reveals that the restoration was originally planned to be completed within five years, but difficulties were beyond expectation. Deadlines finally gave way to ensuring the safety of the pages.

"The project also helped us to nurture new understandings of what restoration should be like," Chen says.

New chapter

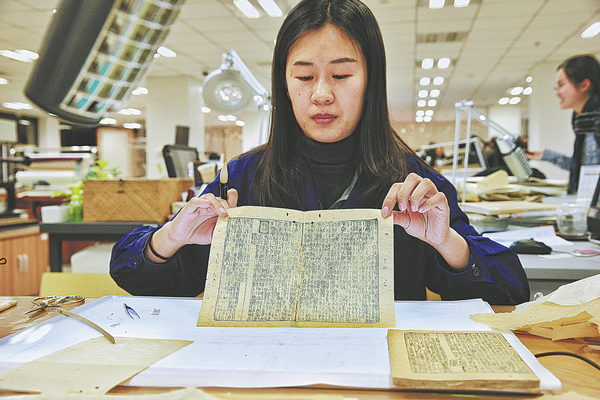

Following her experienced tutor Zhu, Cui feels lucky to be allowed access to the literary treasure trove so soon after starting work at the National Library of China. For book restorers in the past, it would probably be unimaginable.

"An old-time master teaching book restoration wouldn't allow their apprentices to participate in major work until they had practiced a range of skills and done minor jobs for at least a decade," Zhu says.

"That time-consuming process was a good way to pass down the techniques, as authentic and completely as possible, from one generation to another," he continues. "But we're getting old and China severely lacks ancient book restorers. We couldn't afford to wait for so long."

Therefore, Zhu recruited fresh faces, like Cui, into his team. The earliest days were tough for the novice, but Zhu says the Tianlu Linlang project has proved that young restorers, who have a better educational background than their predecessors, can grow more quickly after honing their skills during the most important missions.

Cui and other young restorers from the National Library of China were not the only ones to take up the task. Under the framework of the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books, 12 restorers from key institutions nationwide, including Nanjing Library, Shanghai Library, and Shandong Library, were selected for the Tianlu Linlang project. Some graduate school students from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, majoring in ancient books, also took classes at the project's restoration site.

The entire working process was recorded in detail in videos for historical record.

"The restoration can greatly boost the perception of intangible cultural heritage nationwide, thanks to the participation of young people," Zhu says.

Restoration concerns more than tradition. In labs, modern scientific analysis of the abundant varieties of ancient paper in the volumes of Tianlu Linlang also helps to build a database that will efficiently help follow-up searches for the right material required for upcoming conservation projects.