|

|

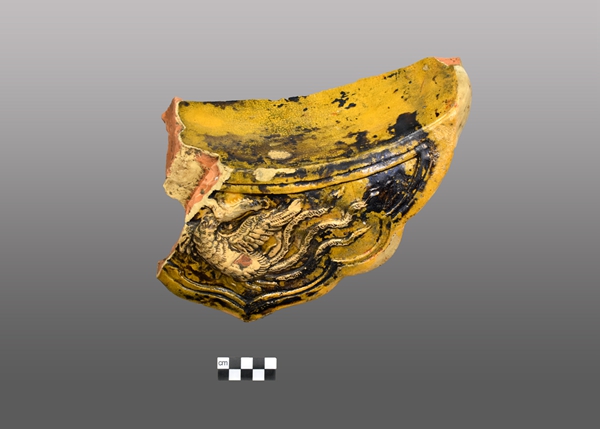

Tiles unearthed in the "Jinshuiqiao" area of Zhongdu feature dragon and phoenix patterns.[Photo provided to China Daily] |

Wider horizons

Wu and Yang agree that the fact that there's little archaeological evidence related to the Forbidden City's infancy makes doing research in the Palace Museum difficult.

"Just like ordinary people decorate their new homes, Ming and Qing emperors kept renovating and redesigning the palaces," Yang says.

"Many buildings in today's Palace Museum were rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty, partly due to fires throughout history. And most remaining Ming structures like the Hall of Central Harmony are from the dynasty's middle or late periods."

The surviving imperial Ming court files are also scarce. So, the Forbidden City's earliest history is mostly sealed underground, Yang points out.

"Fortunately, the Forbidden City is very well preserved as a zenith of Chinese palace construction," Wu says.

"However, because it's so intact, we rarely have the chance to conduct underground excavations on the (UNESCO) World Heritage site. After all, we can't demolish those buildings.

"But Zhongdu presents a perfect specimen to understand the Forbidden City's early-period layout, craftsmanship and design due to their similarities. And the Forbidden City also largely guides our research in Zhongdu."