Inclusive characters

To learn something different from European culture, De Laurentis went to the University of Naples "L'Orientale" — one of the oldest schools of Sinology and Oriental studies in Europe — to study Chinese in 1996. Two years later he arrived in Beijing for the first time, where the young Italian enjoyed browsing bookstalls and shopping for calligraphic reproductions, particularly drawn to the variety of fonts on shop signs and light box advertisements lining the streets.

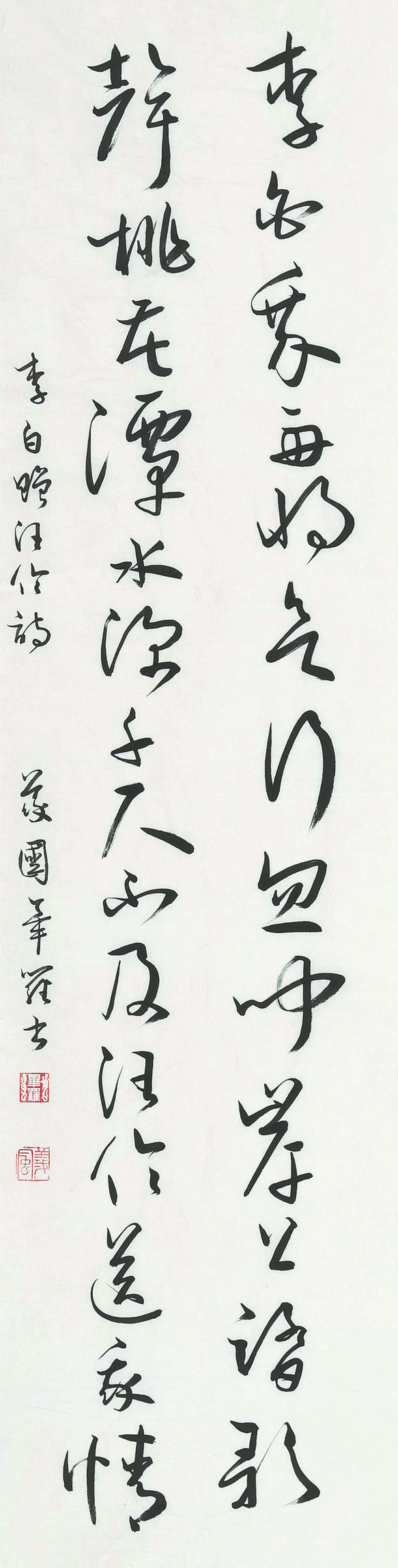

Back in Italy in 1999, he began systematically learning calligraphy with calligrapher Wang Chengxiong from Shanghai. He has since kept the habit of regularly copying works of ancient masters, not only as a hobby but also as a research approach.

"It feels like having direct conversations with ancient literati. The subtleties in the brushwork, structure and composition are not always discernible to the eye but can be understood only through dedicated practice," says De Laurentis.

He particularly favors Tang Dynasty calligrapher Ouyang Xun, whose kaishu (regular script) works are vigorous and forceful, yet with orderly strokes, as well as rigorous and well-proportioned structures.

Starting from the history of calligraphy — handwriting is a fundamental aspect of intellectual life — De Laurentis gradually expands the scope of his research to the overall cultural temperament in ancient societies.

He has also translated 120 poems by Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai into Italian and introduced the master's life stories and spirit to his fellow countrymen based on extensive research.

The Sinologist's Chinese name Bi Luo is derived from a sentence in the Taoist classic Chuang Tzu (The Book of Zhuangzi), which emphasizes the infinity and inclusiveness of the universe, therefore suggesting that it's better to accept and adapt to changes rather than being stuck in obsessions.

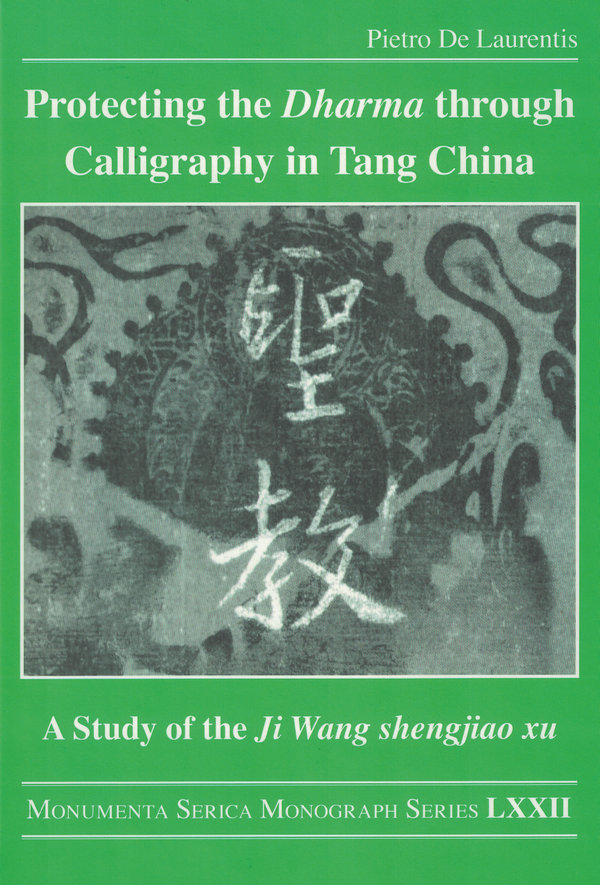

De Laurentis is one of the few Sinologists specializing in Chinese calligraphy. In his observation, Western artists and scholars on textual cultures are more interested in and sensitive to the beauty of Chinese characters and the texture of brushstrokes than Sinologists.

By comparing Wang Xizhi — the most well-known calligrapher in Chinese history — to da Vinci, he hopes Westerners can immediately grasp the extent of Wang Xizhi's significance and influence in China and throughout East Asia.

"On the other hand, it's a reminder for Chinese scholars that they should treat their calligraphy traditions with the same reverence that Italians have for masters like da Vinci and Raphael."

There's no denying that Chinese people are more knowledgeable about Western arts than Westerners are about those of China. Yet, great artists would naturally become aware of other artistic traditions, he says.

In December, on academic bimonthly Contemporary Artists, De Laurentis published an essay on the historical and contemporary spread of Chinese calligraphy in the West, summarizing his 10 years of research and reflections on this topic.

He mentions that by the time renowned Chinese painter Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) visited Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) in Nice, France, in 1956, the latter had already been studying ink painting and asked Zhang technical questions.

And among the numerous merchants, diplomats and monks visiting China throughout history, "there must have been people like me who, in addition to completing their missions here, also felt connected to the culture and spirit of China", says De Laurentis. "We should not eliminate this possibility."

Zhang Jingye, a doctoral candidate at the Guangzhou academy and the Swansea College of Art at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, says that when tutoring her doctoral dissertation on the imitative tradition of calligraphy, De Laurentis attaches great importance to the sensitivity to the art of calligraphy as the foundation of her study.

"The most fundamental aspect of calligraphy research is the calligraphic art itself rather than constructing the history of calligraphy from the perspective of the sociology of art or anecdotes of artists. Western studies on Chinese art history often lack the investigation of the captivating nuances of the strokes. In my case study, I've focused mainly on appreciating these subtle aspects," Zhang says.

One day last February, while she practiced calligraphy with a small brush at the British Library, a local woman observed her for a long time and was impressed by the richness of the brush movements.

"The beauty of Chinese calligraphy is not abstract. It simply takes time and patience," she says.

Lin Qi contributed to this story.