From the outside, the cave at Tam Pa Ling in northern Laos does not look impressive. But descend the path into the cool interior and a natural cathedral is suddenly revealed.

For more than 20 years scientists from around the world have been working with their Lao colleagues to trace the evolution of man's journey into the region.

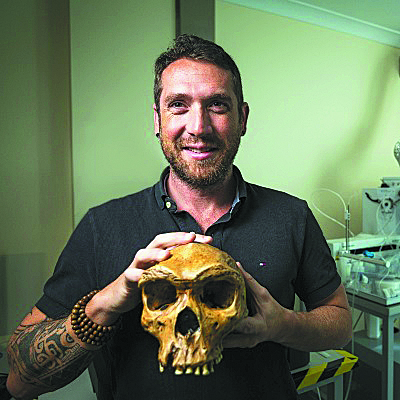

Renaud Joannes-Boyau, an associate professor at Australia's Southern Cross University, said just walking into the cave is a "humbling" experience.

He has been working on and off at Tam Pa Ling for around 10 years, and each visit is as "exciting as the last", he said.

"The site itself is like a cathedral with the ceiling 6 to 7 meters high. And the arc lights set up around the various excavations cast an eerie glow. It is quite beautiful … almost biblical."

Joannes-Boyau's specialty is geochronology, which is the science of determining the age of rocks, fossils and sediments by using "signatures" embedded in the rocks.

Worldwide efforts

He is just one of dozens of scientists from around the world who have been working at the Tam Pa Ling site.

A leading researcher on the dating of the human evolutionary journey and understanding the life strategies of our ancestors, Joannes-Boyau's work has taken him around the globe.

Born in France, he studied at the University Bordeaux where he gained degrees in science, archaeology, and a master's in applied physics.

After completing his master's in 2006, he moved to Australia where he completed his doctorate in geochronology and geochemistry at the Australian National University in Canberra.

His passion for geochronology started when he was at school in France.

"I had this fascination about age and just how important it is to understand the succession of species in human evolution.

"I guess I knew then that this was the path I wanted to take," he said.

Joannes-Boyau said his biggest influence was probably his grandmother.

"She was very influential in my life. She took me around Europe to see many archaeological sites. She seeded knowledge, academic endeavor, archaeology and history."

The geochronologist said he still has the same passion and excitement for every new project he works on.

The first project he took part in was in North Africa at a cave called Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, which contained the oldest well-dated evidence of Homo sapiens.

Joannes-Boyau's research focuses on the development and application of direct dating methods and micro-analytical techniques to key questions in archaeological sciences, such as the timing of human evolution, interaction with the surrounding environment as well as hominids' diet and early life history.

So far, his work has taken him to every continent apart from Antarctica.

"I have been fortunate to have a job which has taken me to many incredible places and where I have met many amazing people. It has introduced me to new cultures and ethnic groups," Johannes-Boyau said from his office at Southern Cross University.

But the most important thing he has gained so far from his career, he said, has been the "emergence and adaptability of our genus and species and how we have adapted and shaped our environment".