Cultural connotations

In Chinese, a bamboo node, or jie, has the same pronunciation as another Chinese word denoting loyalty and rectitude. The association was routinely alluded to by those who considered themselves occupants of moral high-ground in times of adversity.

That adversity could be brought on by the sweeping force of history, whose course is strewn with the casualties of power struggles. The successive emperors of a particular monarchical regime claimed to rule by the mandate of heaven, until that was lost to a contender, often following bloody, protracted warfare. But "a change of the sky", as Chinese would call it, had often failed to produce an immediate change of mind.

Yang Han (1662-1722) and Zhu Ruoji (1642-1708), both of whom painted bamboos and were featured in the Met show, were born within the two decades during which the ethnic Manchu people from northeastern China defeated the armies of the Ming empire (1368-1644), rode into Beijing on horseback and founded the Qing — the country's last feudal dynasty.

As members of the majority Han people who ruled China in a large part of its history, both painter-calligraphers harbored grievances, not helped by the fact that Yang's father had once served in the Ming court while Zhu Ruoji was the direct descendant of Ming's extended ruling Zhu family.

By filling their bamboo paintings with swooshing wind and spattering rain, the two men highlighted the plant's quality of bending without breaking, apparently inspired by the strength of the reed to offer their own quiet resistance.

Or, to maintain their "public posture and identity" — to use the words of Dolberg — one that allowed them to stay within a circle largely populated by Han scholars who saw themselves as Ming's "leftover subjects".

How steadfastly they had clung to that identity, however, is debatable.

In 1684, a decade before Zhu made that painting, he was given an audience by Emperor Kangxi, who, during a tour of the rich southern part of the Qing empire, stopped by a Buddhist temple Zhu was residing in at the time.

When that experience was repeated five years later in another Buddhist temple during another of the emperor's six southern tours (this time, Kangxi, upon seeing Zhu who went by the name Shitao, was able to recognize him instantly), the man was grateful enough to inscribe himself in a painting he presented to the emperor as "your faithful subject, the monk". He was elated enough to travel from Yangzhou to Beijing in the hope of capitalizing on what turned out to be fleeting fame.

By doing so, the painter had plainly ignored the fact that as a 3-year-old, he was secretly removed from home and taken into a Buddhist temple by a house servant, following the killing of his father, a vassal lord, amid all the rivalry for the throne of an empire which by that time had largely ceased to exist.

In Beijing, Zhu wanted to serve the Qing emperor not just as a painter and was deeply disappointed when the capital's rich and powerful, whom he tried to ingratiate, refused to see him as anything other than someone who could paint.

He returned to Yangzhou in 1690, 63 years before Zheng did the same, where he painted for the next 18 years until his death, leaving behind a treasure trove of works that would greatly influence latecomers, among them the "eight eccentrics of Yangzhou".

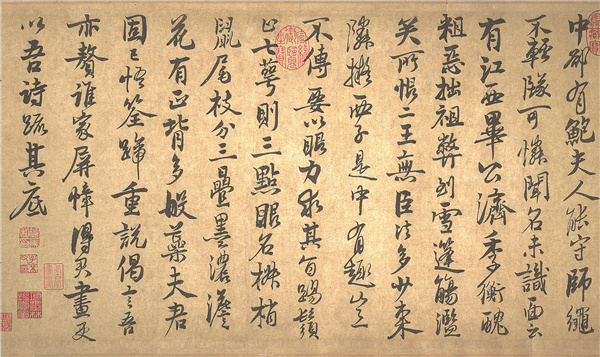

In that particular painting displayed in the Met, Zhu quoted famed Song Dynasty poet-writer Su Zhe (1039-1112) commenting on his cousin Wen Tong (1018-1079), who in turn was worshipped as the finest bamboo painter of all time.

Describing Wen as "sauntering and slumbering", "feasting and resting" amid bamboo, Su concluded that "only after much observation can one fully comprehend bamboo's transformation and self-renewal".