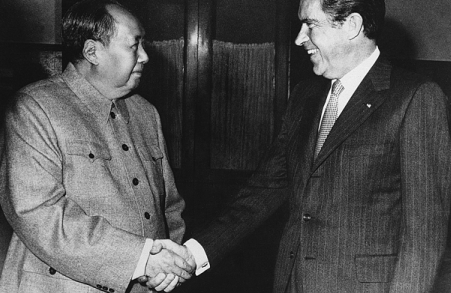

Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon greet one another the same day. CHINA DAILY

Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon greet one another the same day. CHINA DAILY

That said, Freeman admitted that to arrange for the US"an honorable exit" from the war in Vietnam topped Nixon's agenda."It was surprising and very fortunate that the American public understood the strategic importance of what Nixon was doing, and the bravery it involved."

"Bravery" also due to the mounting pressure from "friends and allies", among them Japan and the Nationalist government in Taiwan, said Freeman, who soon found out that he and the other two people on Nixon's interpreting team made up "an odd group".

"One of them was rabidly pro-Kuomintang (the Chinese Nationalist Party)-he went off on a hunting trip in Taiwan with Chiang Ching-kuo right after the trip. The other was a 'Taiwan-independence' advocate. (Chiang Chingkuo was the eldest son of the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan.)

"They were brought in as my backup and were never used for interpreting," says Freeman, who, to his own surprise, saw himself refusing to interpret for the president the first time he was asked to do so, one and a half hours before the Nixons attended the welcoming evening banquet at the Great Hall of the People, where they were guests of Zhou.

"I was called over to the president's villa and was told by Dwight Chapin, acting chief of protocol for the trip, that the president would like me to interpret the banquet toast," he said.

Having done the first draft for the toast and knowing that his original version had been altered with the insertion of some English translations of chairman Mao Zedong's poems, Freeman asked for the text and was bluntly told that there was no text.

He then confronted Chapin with the truth. "If you think I'm going to get up in front of the entire Chinese politburo and ad lib Chairman Mao's poetry back into Chinese, you're nuts," he told Chapin, whom he called Nixon's "gate-keeper".

At that point, Chapin said "all right". He then "took the text out of his pocket and gave it to the Chinese", who later did the interpretation, according to Freeman. After the trip, Freeman learned that it was Richard Solomon, a member of the US National Security Council, who struck in the lines "to ingratiate the president with the Chinese leadership". Solomon played a pivotal role when the Chinese table tennis team visited the US in April 1972, barely two months after Nixon's trip to China.

In retrospect, Freeman considers the episode a pointed example of the extraordinary measures the Nixon administration had taken to maintain secrecy, without which "the trip wouldn't have been possible", given the domestic opposition he might have faced.

"Nixon had a predilection for using the other side's interpreters, because they wouldn't leak to the US press and Congress," Freeman says.

It is also worth noting that on the afternoon of the same day, Nixon met Mao at his residence for an hour. That was not on the day's schedule, and Nixon, who was given short notice, took along with him only Kissinger and Winston Lord, Kissinger's special assistant, who became ambassador to China between 1985 and 1989.

"The reason (for the sudden meeting) was because Mao was in very frail health at the time," said Freeman who, like the rest of the entourage except for Kissinger and Lord, did not get the opportunity to see the Chinese leader.

His memories of his encounters with some Chinese officials and diplomats have endured. At some point on the trip he was offered a cigarette by Li Xiannian, who became Chinese president in 1983. "I had given it up nine years before, when I was in law school in the early '60s. But I took it and have smoked ever since," Freeman says.