|

|

A brick painting of a Silk Road courier charging on a horse, unearthed in Gansu. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

"Archaeological excavations in Palmyra, an ancient city in presentday Syria, has yielded silk fabrics decorated with the signature local grape patterns but were woven using Chinese methods. The possibility is that they were custom-made by Chinese weavers for customers they probably never got a chance to see," he said. "The famous Persian brocade, for example, had seamlessly woven Persian-Arab motifs into raw Chinese silk bought from Sogdian merchants who, thanks to their monopoly of trade on the Silk Road between the 4th and 8th century, were enviously dubbed Jews of the ancient world."

Many of these men, says Zhang Deshui, vice-director of the Henan Provincial Museum, later stayed without ever returning to wherever they had come from. Today their tombs are found in large numbers in Luoyang, a city in western Henan associated with golden eras of both China's Han (206 BC-AD 220) and Tang (618-907) dynasties .

|

|

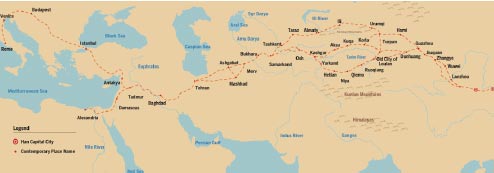

The Silk Road during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). [Huang Huo/For China Daily/Kong History Museum] |

"It is these common people-the anonymous trekkers who manned the caravan heading for the unknown-who have filled the Silk Road story with all its touching details and remarkable aspects. Their distinct images-in conical cap and slim, open-collared Central-Asian style outfit-also appeared inside the tombs of many local Chinese, in the form of both murals and pottery figurines."

Another item, apart from the renowned Chinese silk, that had become so coveted as to serve as a hard currency on the Silk Road, was spice. A couple of dozen types of different spices-mostly used as fragrances for the wearers and their ambience-were frequently traded along the route, Ge says.

"The spice traveled in the opposite direction to the silk, from the Indian subcontinent to major Chinese cities. The silk road entered its heyday during the Tang Dynasty, an era of immense social wealth.