|

|

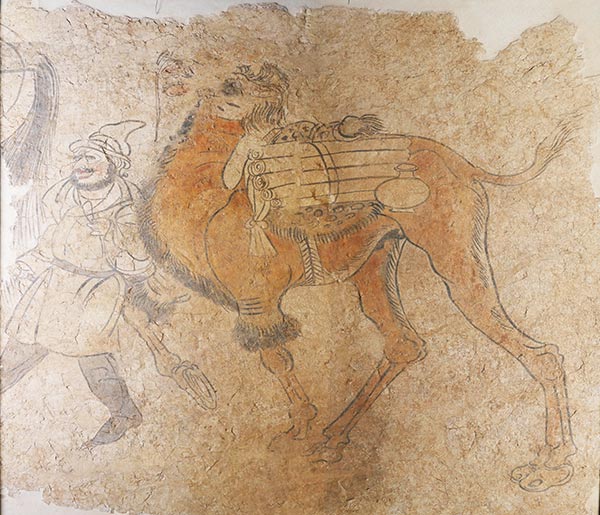

A Sogdian merchant with his camel carrying rolls of silk, appearing on a Tang-Dynasty mural painting unearthed in Luoyang, Henan. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

An example was a gilt silver high-stem vase unexcavated in a tomb site in northwestern China's Ningxia Hui autonomous region, through which the ancient Silk Road went. With three pairs of embossed characters wrapped around its body-both male and female, the vase evokes scenes from the much venerated ancient Greek epic Iliad (the vanity-fueled dispute for the golden apple among three goddesses, the seduction of Helen by Prince Paris of Troy and the return of Helen to her husband, King Menelaus of Sparta.)

The neck and bottom of the vase is rimmed by continuous beads, a typical decorative pattern from the Sasanian Empire (224-651), an empire set up by the Persians in what is now Iran.

"Here we have from the burial ground of a Chinese general a beautifully crafted work of art mixing Hellenistic and Persian influences," Ge said.

Judging by the evidence, the scale of this cultural convergence lies far beyond the imagination of Emperor Wudi of China's Han Dynasty, who ruled between 141 BC and 87 BC. In 139 BC Wudi sent out a convoy on a westward journey that would eventually lead to the opening of the Silk Road.

The original goal of the powerful emperor was to obtain an alliance with the Kingdom of Dayuezhi, located in what is now Central Asia, against the marauding Xiongnu troops. A large confederation of Eurasian nomads that existed between around 300 BC and AD 450, these ferocious horsemen proved themselves to be the ultimate scourge for Wudi and those who preceded and followed him. The convoy was led by Zhang Qian, the man known in China today as the "tunnel digger of Xiyu" (Xiyu means the western regions.)