|

|

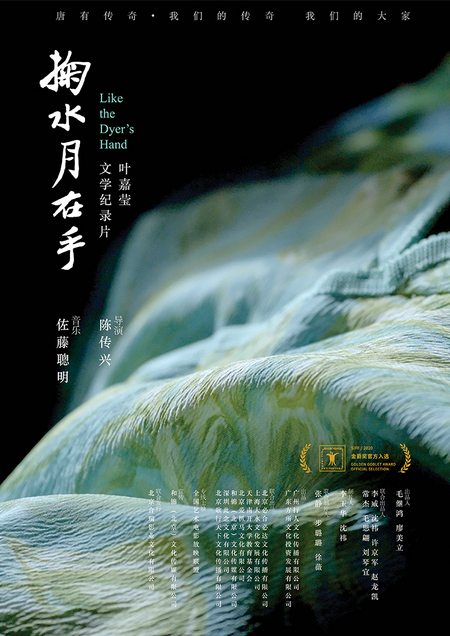

The film poster.[Photo provided to China Daily] |

She graduated in her 20s from Fu Jen Catholic University, which later became part of Beijing Normal University, and started teaching literature at a secondary school. In 1948, toward the end of the Chinese civil war, Yeh married Chao Chung-sun, who worked for the Kuomintang navy. The couple moved to Taiwan the next year after the establishment of the People's Republic of China.

Yeh found work at a school in Changhua. However, not long after arriving in Taiwan, Chao was arrested on suspicion of being a spy and imprisoned for three years.

Yeh, who had given birth to a daughter only months earlier, was also briefly detained by police but no charges were brought against her.

"After that, I only lived in the sitting room of my relatives with my newborn daughter," she recalled in a previous interview.

She lived with relatives until her husband's release in 1952 and continued to teach.

She later worked at National Taiwan University. However, her husband suffered from depression that developed in prison and it severely affected family relations, she said in an interview earlier.

In 1966, the family moved to the United States, where Yeh taught Chinese poetry first at Michigan State University and then at Harvard University. They moved to Canada in 1969 when Yeh was offered tenure at the University of British Columbia, where she is professor emeritus.

Tragedy struck again in 1976, when Yeh's eldest daughter and son-in-law were killed in a road accident in Toronto. Chao died in 2008.

"Enormous sorrow and hardship as well as devotion to poetry have propelled me to gain an outlook on life that I don't mind any success or failure, gain or loss," Yeh says in the documentary.

The film also highlights Yeh's commitment to Chinese poetry. Studies in Chinese Poetry, the 1988 book she co-wrote with Harvard professor James Hightower, is recognized for its profound impact on the global appreciation of Chinese poetry.

Yeh has also introduced the German aesthetician Wolfgang Iser's explanation in "potential effect" to Chinese lyrics to highlight the aspect of Chinese aesthetics. She has adopted French semiologist Julia Kristeva's outlook to express the connection between ego and Chinese lyrics and poetry.

The film shows places connected to ancient Chinese poetry. The Buddhist frescoes in the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, stone inscriptions and a variegated old bronze mirror in the Forest of Stone Tablets in Xi'an and Tang Dynasty (618-907) relics are used as backgrounds during Yeh's narration.

"After thousands of years, it was hard for us to make a replica of the natural scenery of the Tang Dynasty and Song Dynasty (960-1279), so we made efforts to showcase the tremendous changes in the four seasons-the moments in poems," Chen says.

The film is divided into seven chapters, with the second to sixth chapters named after a part of Yeh's old residence in Chayuan hutong in Beijing, such as the courtyard and west-wing room, because the director wanted to use the scene to show Yeh's life journey.

"This year, the world has been hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, and I hope the film helps the audience to reflect on their experiences and emotions," Chen says.

Yeh says she has been staying at home this year and appreciating Chinese poetry.

"Sometimes I forget the time when I'm reading."

Contact the writer at yangcheng@chinadaily.com.cn