|

|

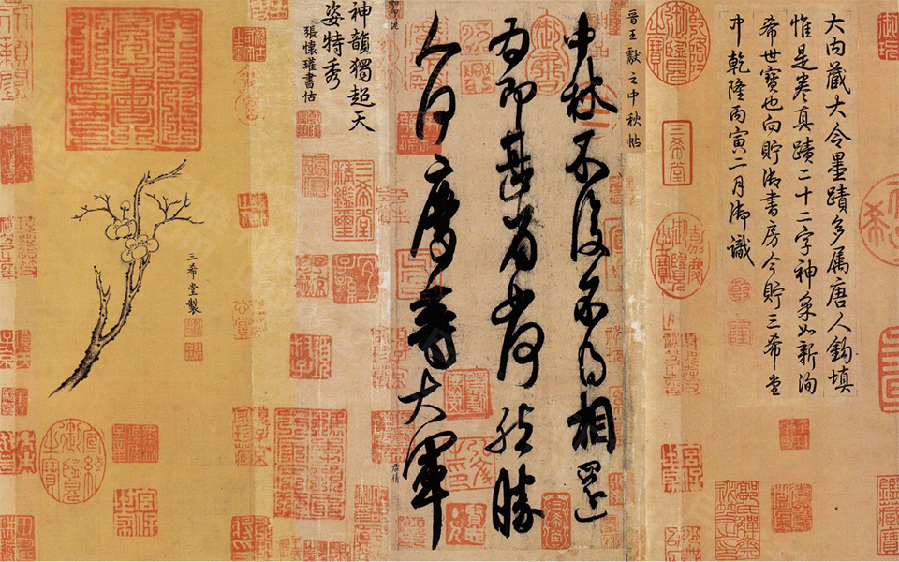

Zhong Qiu Tie by Wang Xianzhi (part) [Photo/yueyaa.com] |

Calligraphy in ancient China was critically important for Chinese literati.

Since the practice of the imperial examination, calligraphic skill may change the fate of those examinees. It was generalized that, since so few were able to receive formal education, their intercultural ability and their qualification to serve the emperors correlated with calligraphy.

Moreover, the examiners might not have enough time to go through all the essays, and they tended to rank candidates based on calligraphy rather than contents. Therefore, calligraphy somewhat became a strong indicator for talent and promotion.

Even in daily lives, people with calligraphic skills were highly respected and in high demand for letters, contracts, Buddhist scriptures, as well as decorations for weddings and funerals.

Nowadays, zhongtang, which consists of three pieces of calligraphic works and a water-color painting, is the most elegant feature of the living room and is still popular in rural areas of northwestern China.

It is a meticulous plan to set up the zhongtang in order to impress the guests. The choice of calligraphy and, most importantly, its meaning reflects the social status in the neighborhood and is considered as one of the most important assets for fortune and prosperity for generations.

Although urbanization offers limited space required for traditional zhongtang, it is still a common practice for many to assemble calligraphic works in the living rooms. In modern China, calligraphy in such formats as mottos has emerged as an expression of aesthetic philosophy and personality.

Calligraphy used to be a privilege among the well-educated elites. Nowadays, significant reduction in poverty and illiteracy encourage more and more people to practice calligraphy. As much as recreation, physical fitness and artistic appreciation, calligraphy is becoming a part of life among many Chinese people. With numerous calligraphy training courses and interest groups among local schools and communities, plus various calligraphic competitions, exhibitions and auctions, today is another Golden Age of Chinese calligraphy.

About the author:

Guo Jiulin is professor of Dalian Nationalities University (DNU) and the institute director of Comparative Study of Chinese and Western Cultures at DNU