|

|

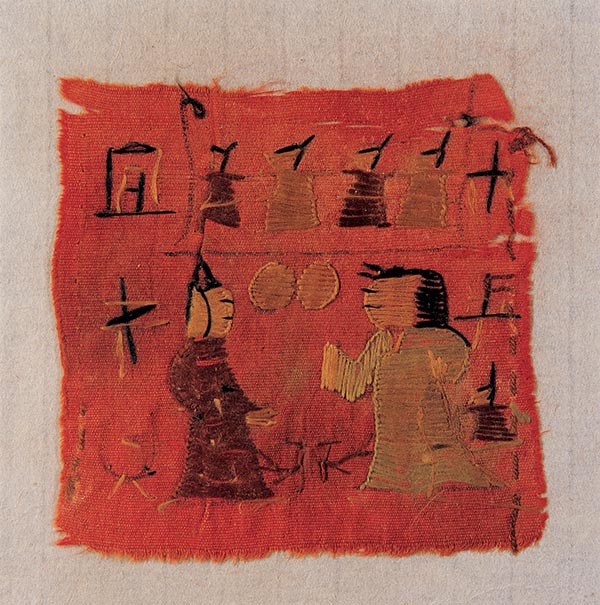

Embroidered silk unearthed from a tombsite in Gansu, provided by Gansu provincial Museum [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Paralleling this fast development of the State-sponsored textile industry was the appearance of silk on the extended trade route which, after nearly two millennia, would be named after it. It also fueled a craving for the brilliant fabric that has proven enduring. (Coins discovered in a tomb in Shaanxi that were minted by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (483-565) are linked with the Byzantine purchase of Chinese silk.)

One typical image born out of this craving involves that of a camel. Pottery renditions of the pack animal have turned up in large quantities in ancient tomb sites along the route, from Xi'an all the way to what is today Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in China's far west, bordering Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The area, part of what is known as Xiyu, or the western regions, is traversed by the Silk Road, the route for every caravan that traveled between the Chinese Empire and the Eurasian countries in Central Asia and around the Mediterranean.

"The few things you would usually find on the back of a camel is a wineskin or water flask, a Central Asian-style musical instrument for plucking and a pair of sacks loaded with thick rolls of fabric or locks of raw silk," Zhao says.

"Silk became the No 1 merchandise on the Silk Road partly because it is light in weight, so is easy to carry in relatively large quantities. Its warm reception by people far and wide not only yielded vast profits for the middlemen - mostly Sogdian merchants who routinely sold the much sought-after commodity at a price a hundred times higher than its initial purchasing cost - but also made silk the de facto hard currency on the trading route.