|

|

[Photo provided to China Daily] |

In The Peony Pavilion, his most renowned play, Tang elevated the dream to a level that Sigmund Freud would have recognized. It is the subconscious world of the protagonists, especially Du Liniang, the aristocratic young lady who whiles away her youth in a gilded cage. It is not a conventional love story because she had not seen or known the young man before her pining consumes her. One can argue that she was not in love with a specific person, but with the notion of love itself, corporal love that can only be suggested in that environment.

Even though Liu, the young man, had dreamed of her, it is his discovery of her portrait three years after her death that plants the seeds of obsession. He at least knew Du had existed. But for Du, that dream, full of erotic innuendo, is a path to the freedom that young women of imperial China were normally denied-to love someone without family intervention.

It is ironic that the eroticism permeating the play and the eventual resuscitation of the female lead from her grave seem toned down or removed for the sake of political correctness, depriving the tale of its psychological depth and reducing it to pure romance.

Of all Shakespeare's works, the dream features most prominently in A Midsummer Night's Dream. The forest near Athens is akin to the family garden in The Peony Pavilion, a neighboring quarter that harbors the forces of seduction and sets free the desires of the young. It is not the island in The Tempest, nor the city of Verona for the star-crossed lovers. Despite the use of magical juice, it is not passion that is fueled but an amorous atmosphere in both Shakespeare's Dream and Tang's Pavilion. One can imagine Liu and Du singing a duet in that forest in the same way Puck would find himself at home in Du's garden.

For the deux-ex-machina happy ending, Pavilion is evocative of sadness that is absent from Shakespeare's Dream. But lyricism and earthy humor are present in both plays. And both tales can be sung or danced because they lend themselves to other forms of performing arts. Pavilion, intended as an opera, has also been adapted as a play but has been less successful.

On April 10, in Suichang, Zhejiang province, where Tang served as a local official and where he started writing Pavilion, two dozen scholars from China and the UK floated ideas and questions:

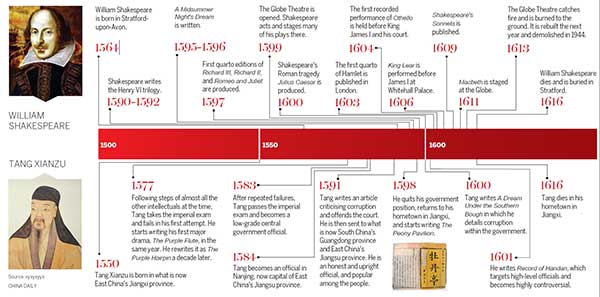

Shakespeare was a professional dramatist while Tang was a civil servant who happened to pen a few plays and thousands of poems.

They both represent peaks in culture, but we should refrain from measuring which peak is higher and focus instead on what's unique about each of them.

How can we free ourselves of the limitations of culture so that we can have better exchanges?

The comparison of Tang and Shakespeare can serve as a point of departure for meaningful conversations about art, literature and cultural inspirations, rather than being an end in itself.