|

|

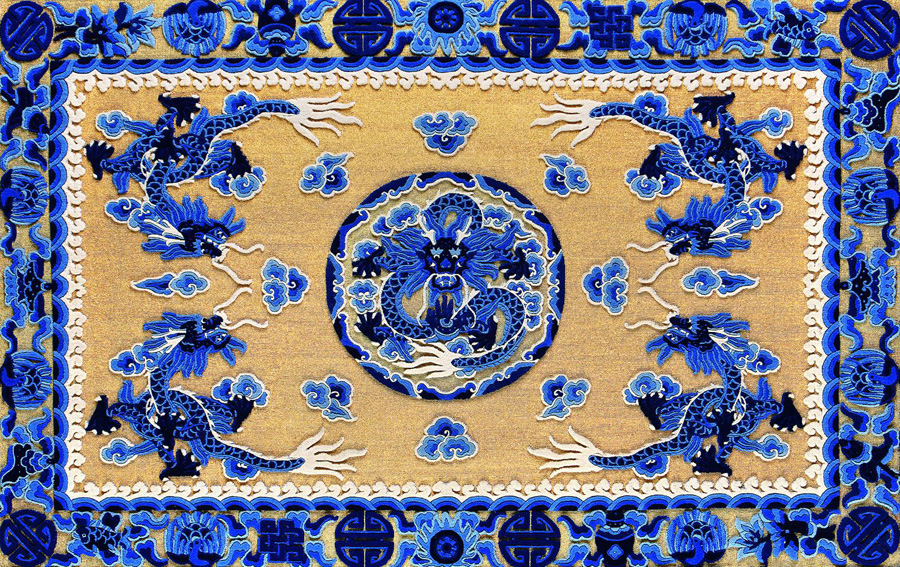

A palace carpet showcased at the "The Great Spirit of Craftsman - Eight Marvelous Handicrafts of Beijing" exhibition. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

According to Zhong Liansheng, a national-level master of cloisonne enamel, the exhibition represents a revival of Beijing’s traditional craftsmanship, which once endured difficulties.

"Those articles used to be only exported and had low consumption among domestic consumers in the 1980s," Zhong recalls.

And, when their export demand would fall, learning the skills of making such crafts weren’t popular as well. "The old master-apprentice model was in crisis."

It is therefore necessary to train potential inheritors when they are young, he says.

"A good thing is that many exhibits today are actually works of students in schools," he says.

Wang Shijie, head of the Beijing Senior Technical School of Arts & Crafts, says his school now has more than 1,500 students honing their skills in traditional craft.

"If people want to be handicraft masters they must try to excel in their work and create something new on the basis of older models," Wang says.

But inheriting craftsmanship doesn’t mean stubbornly sticking to old ways, he says. And, in some cases, a change of course is inevitable. For instance, ivory carvers have to switch to other fields because elephants should not be hunted.

"Since the Beijing handicrafts are rooted in daily life, they can also gradually evolve with change in people’s aesthetic tastes, but the traditional skills need to be maintained."