|

|

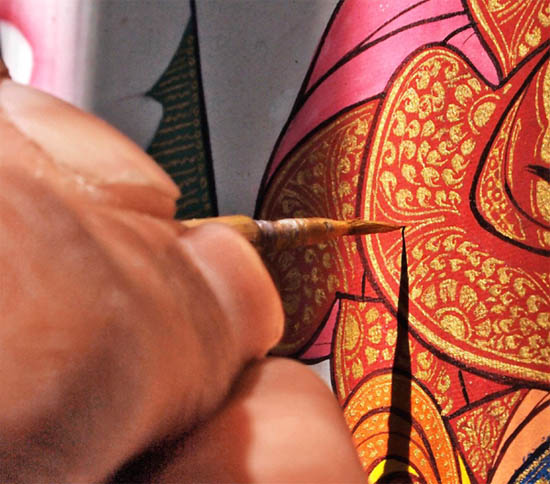

Thangka painting involves highly skilled, geometric painting on cotton or silk.

|

Forty-six-year-old Manzhong Norbusitar is a national inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage of Thangka painting, a traditional Tibetan art form. The fourth generation in a line of Tibetan artists, he showed a strong interest in Thangka from a young age. Thangka painting involves highly skilled, geometric painting on cotton or silk and usually depicts a Buddhist deity, a ritual scene or symbol. Norbusitar learned the necessary techniques from his grandfather, famous Thangka painter Dhawa Dhondrup, and was later apprenticed to renowned masters Karchen Lozang Phuntsog and Wuchen Ngadun to learn more about Thangka art and related Buddhist knowledge.

Norbusitar uses his brush to record and disseminate traditional Tibetan culture. In doing so, he is making ceaseless efforts to cultivate a fifth generation of Thangka painters and encourage more students to study the art form.

Childhood Affinity with Thangka

The Chalalubu Monastery is on the hillside to the west of the Potala Palace square. Norbusitar’s studio, the Mensar School Thangka Art Development Center, is at the foot of the hill. Norbusitar is no great talker, but is very happy to tell others about his Thangka and paintings.

Norbusitar was born in 1967 in Xigaze, Tibet. “Five generations of my family have been dedicated to painting Thangka of the Mensar School.” At 12 years old, he started learning to paint from his grandfather Dhawa Dhondrup and continued under his tutelage until he was 19.

In 1987, the Tashilhunpo Monastery built a shrine to house the remains of the Fifth to Ninth incarnations of Panchen Lamas. Following his grandfather, Norbusitar participated in painting the murals adorning the tomb. It was at that time that he was discovered by Karchen Lozang Phuntsog, staff painter for the Tenth Panchen Lama, who became his master. He then studied Tibetan Buddhism, especially the art and skills of painting the Sakyamuni Buddha and various Buddha statues of the Vajrayana Sect. During these years, Norbusitar studied sutras, the proportion of statues and scale, and reproduced paintings of various clothing and statues. He also learned how to make and effectively use different tools, like canvas, brush pens and colors. Norbusitar also painted murals for many monasteries in Xigaze, including the Sakya Monastery and Tashi Gephel Monastery.

After years of apprenticeship and practice, Norbusitar gradually obtained a better understanding of the painting theories and skills of the Mensar School. His works were highly praised and many monasteries invited him to paint Thangka and restore damaged murals.

Since 2005, Norbusitar has independently taken on the task of restoring and reproducing the murals in the Mandala Hall of the Potala Palace. He replicated damaged murals in Thangka paintings of reduced proportions, so as to preserve the precious artwork.

“Copying is not simply imitation,” Norbusitar said. “It is a science, a kind of understanding, and an innovation.” Some parts of the murals he replicated were very badly damaged. Certain aspects were hard to distinguish, and the original paintings on which they were based couldn’t be found anywhere in Tibet. It made the work very arduous. But Norbusitar thought that if it meant cultural heritage could be preserved and passed on to future generations, it was a worthy challenge.

To protect the relics, Norbusitar had to work in dim light with a brush pen in one hand and a magnifying glass in the other. He first had to paint the murals onto a white cloth, and then restore the damaged or missing pieces of the mural one at a time.

Some people viewed Norbusitar’s task as a pointless exercise that could hinder his capacity for artistic innovation. But Norbusitar realized that the prime task of protecting intangible cultural heritage is to pass on the traditional techniques and skills; only by mastering traditional skills yourself can you make a natural breakthrough and improve.

We Recommend: