ED WRAY/CHINA DAILY

Students attend a Mandarin language class at a State senior high school in Lamongan, Indonesia. For decades, the teaching of the Chinese language was forbidden in Indonesia, but latterly Indonesian officials have decided to make Mandarin mandatory for all high school students.

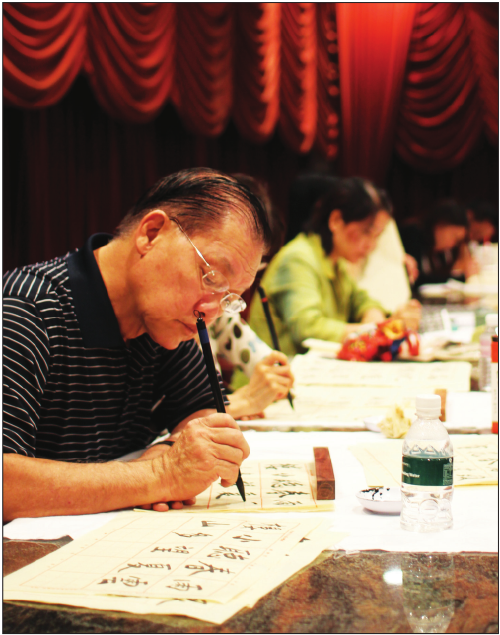

CHINA DAILY

The Singapore Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry holds regular classes to promote Chinese culture.

CHINA DAILY

Chen Yi Ling (far left), a Chinese Malaysian posed with her teachers and fellow students during her three-month Mandarin course at the Beijing Language and Culture University in 2009.

Chinese Malaysians work to brush up skills in proper Mandarin, reports Elaine Tan in Kuala Lumpur.

Samantha Tan, 39, is what Malaysians refer to as a "banana", a term that describes an ethnic Chinese who cannot speak, read and/or write in Mandarin. This ranges from complete ignorance of the language to having a decent command of one or two of the three skills.

"Growing up, we spoke Mandarin at home, but I've always wanted to do a 'tuneup', especially since Malaysian Mandarin isn't considered proper Putonghua. So going to China to study Mandarin was on my 'bucket list' of things to do," said Tan, who is not able to read or write the language.

When her then boyfriend(now husband) found employment in Shanghai, she opted to give up a cushy job in investment at an insurance firm to pursue her dream.

"It was a difficult decision. I agonized over it for almost three months. But in the end I decided to leave because this was an once-in-a-lifetime chance. I felt I might regret not doing it."

Tan arrived in Shanghai at the end of 2002, with a place at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Besides reading, writing and speaking Mandarin, she picked up calligraphy, Chinese painting and tai chi as electives during two semesters at the university.

"I think I did more in that one year than in the rest of my time in Shanghai!" she recalled.

Like Tan, Chen Yi Ling, 32, also headed to China to learn Mandarin.

"I was on a long break from work and wanted to take a holiday. At the same time, I also had a fascination for modern-day China, Chinese culture and history, and wanted to experience living in China," she recounted. A three-month language program at the Beijing Language and Culture University at the end of 2009 met her needs.

"Bananas" such as Tan and Chen are a minority among Chinese Malaysians, whose Chinese literacy is quite high. In 2012, more than 85 percent of the 6.5 million ethnic Chinese in the multiracial Southeast Asian country were deemed Chinese literate. This is largely due to a vibrant Chinese education system-the only one outside China-that uses Mandarin as a medium of instruction from elementary level through to higher education.

But back when Tan was of school age, urban middle class parents like hers preferred to send their children to national schools, where they were instructed in Malay but given wide exposure to English, even though they (the parents) had received a Chinese education.

"It was exotic for them, I guess. Like how it's exotic now for 'bananas' to send their children to Chinese-medium schools," said Tan.

Laying foundations

Lisa Lim, 38, who also studied in a national school, had long regretted not picking up one of the most important languages in the world. When her husband found a job with a hospitality and real estate development company in China, she jumped at the chance to immerse her children in the language and culture. They moved to Xi'an in 2008 and Guizhou three years later.

Lim schools her daughters, Yin Ching, 11, and Yin Ling, 8, at home, but has hired a Chinese-speaking nanny to help the children pick up the language.

"Through her, we learned the foundations of pronunciation and speaking with the local community in their own dialect. She read to the kids every day and conversed with them."

While the children are under the guidance of a tutor and study further by reading storybooks, watching movies and learning through education programs in Mandarin, Lim works on her own conversational skills by engaging with the locals.

"I don't shy away," she said. "I put on a smile and try simple conversations, although this can often result in funny incidents when I use the wrong words!" she laughed.

Next up in the study plan is hitting the road more often.

"Traveling is part of our 'textbook'. We have already visited the Terracotta Warriors, the Xixia museum of dinosaurs, ancient towns in Zhejiang, Yunnan, Guizhou and Hunan provinces, and cities such as Shanghai. We would like to see more of China to fuel the kids' interest in the country."

For "bananas" it isn't just about mastering their mother tongue; they are also driven by discovering their roots and Chinese culture. This is why they make their way back to their ancestors' homeland even though language classes are readily available in Malaysia.

"Learning Mandarin there is different. In Beijing, you hear the original language spoken purely, free from the influence of other forms of the Han dialect, which is the case in Malaysia. Also, I had the luxury of time to discover the culture and traditions which made learning the language more fulfilling," said Chen of her three months in China.

Tan said that her year at Shanghai Jiao Tong University fulfilled her desire to learn Mandarin and connect with her roots. After completing her studies, she lived and worked in Shanghai for a further four years before returning to Malaysia in 2007. However, she remains enamored of the city.

"Living in Shanghai has spoiled big city life for me. Now, other cities pale by comparison. I was in New York recently and it didn't hold up to Shanghai, where things are always unexpected and surprising," she said.

Her only gripe is that she still cannot sing her heart out at karaoke sessions, because the lyrics are written with the traditional characters used in Hong Kong and Taiwan. On the Chinese mainland the characters were simplified by government edict in the 1950s.

With more Malaysian-Chinese parents sending their children to Chinese-medium schools, "bananas" may soon become a rarity. Rita Sim, author of Unmistakably Chinese, Genuinely Malaysian, said in a 2012 interview with the national newspaper The Star that more than 95 percent of Chinese parents are sending their children to Chinese-medium schools.

Other Malaysians have recognized that China's growing global importance means learning Mandarin is now important.

Rina Mohd, 44, was an early mover. Back in 1991, she set off for Taipei in Taiwan for a three-month language program.

No more stereotypes

"I was trying to do a double major in Chinese language and literature on top of my first major. An immersion-intensive program seemed to be a fast and effective way to learn, compared with taking Mandarin in my second year at the University of Wisconsin where I was studying for my bachelor's degree," she said.

"I'd had lessons with a tutor from the age of eight, so it wasn't difficult to learn the language as an adult. But living in Taiwan helped me see past the stereotypes and appreciate the people more, especially after learning the history."

Even in Kelantan, which is seen as the most "Malay" state in Malaysia, interest in Mandarin is rising, according to a report in The Straits Times. Many are following in the footsteps of the former chief minister Nik Abdul Nik Mat from Parti Islam Se-Malaysia, five of whose grandchildren attend Chinese-medium schools.

"Today, more Malays speak Mandarin than ever before. It's part of the transformation of Malaysia to help us gain a vital business edge in years to come, as China consolidates its economic power," said Najib Razak, Malaysia's prime minister, according to a report in the Chinese-language newspaper Sinchew Daily.

His son, Nor Ashman Najib, spent three weeks at the Beijing Foreign Studies University, where he studied conversational skills and Chinese culture. Earlier this year, he used his linguistic prowess to help his father charm voters during a Lunar New Year radio broadcast in which he spoke fluent Mandarin.

So it should come as no surprise to hear of a Malaysian student on a language program course in Beijing praying at a mosque, fasting for a month and celebrating Eid al-Fitr instead of the Lunar New Year, yet also communicating in Mandarin.

We recommend: