Betty Yao says Thomson's images serve as interesting historical material as well as fine photographs.

In later years, Thomson went on to document the lives of London's homeless, while serving as the official photographer of the British royal family. After his death in 1921, his glass negatives were bought by the pharmaceutical tycoon Sir Henry Wellcome.

The purchase was fortunate, as the Wellcome Library was one of the very few places that could store such fragile glass negatives, though at the time no one understood how valuable Thomson's negatives were.

William Schupbach, iconographic collections librarian for the Wellcome Trust, first came across the three crates in the 1970s, and noticed they were labeled "scratched negatives".

He studied the images in detail and realized they were of historical value. His team then made prints from the negatives and catalogued each photograph. They have since been digitalized.

In 2006, Yao came across them in the Wellcome Library. Upon discovering that they had never been exhibited in China, Yao volunteered to curate the exhibition, and the project went from strength to strength.

In 2009, Yao took the exhibition to four Chinese museums: Beijing World Art Museum, Fujian Museum, Guangzhou Museum and Dongguan Exhibition Center. Subsequently the photographs toured internationally, including to Britain, Sweden, Ireland and the United States.

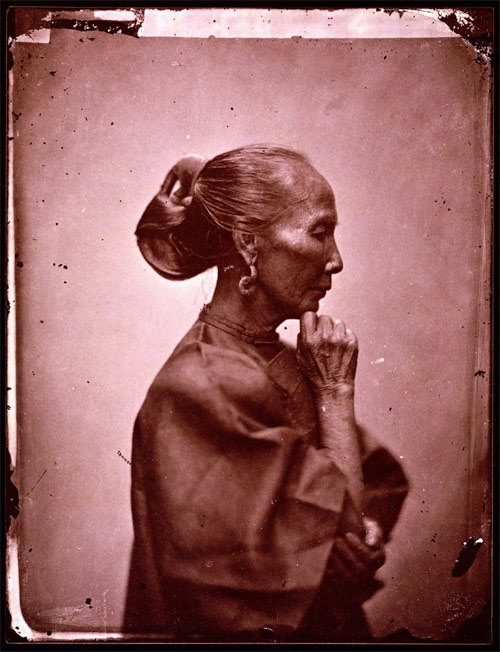

An old woman in Canton (Guangdong).

An old woman in Canton (Guangdong).

The photographs attracted widespread international acclaim.

"The exhibition is astonishing," says Scottish curator Katriana Hazell, who saw the exhibition in Liverpool, England. "How else can we possibly get so vivid an idea of such a wide range of society and life in China at that time?"

"I feel other photographers of that period were colder in their portraiture. I get more of a sense that these photographers were making scientific studies of the local people, especially the poor."

Hazell says details, such as the binding of women's feet, hairstyles and clothing drew her to the collection.

"The wealth of rich detail about street life was particularly fascinating-people gambling, the one of the chiropodist working in the street, the artisans, and especially noticeable, the many, many photographs of women, and their extraordinary exotic hairstyles worn by both grand and ordinary women."

This year, the exhibition is returning to China, to be shown at Shenzhen Museum, Jiangning Imperial Silk Manufacturing Museum in Nanjing and China National Silk Museum in Hangzhou.