There were various reasons for the decline of the Silk Road after Genghis Khan’s grandson Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). One was the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. The Turks’ general encroachment having severed the main overland trade link between Europe and Asia, European traders considered traveling to Asia by sea. Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama made this possible after becoming the first European to navigate a sea route to India. Certain scholars hold that exacerbated desertification also played a role in the fall of the overland Silk Road, as many cities along it were engulfed by sand dunes.

Despite Zheng He and his fleet’s seven successful maritime expeditions between 1405 and 1433 to more than 30 Asian and African countries, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) imposed a ban on sea trade. During much of its existence, China’s doors to the rest of the world were largely closed. In the West, meanwhile, the Age of Discovery had begun. As sea routes were explored and sailing became safer and more reliable, land routes fell out of favor with travelers and merchants.

The Silk Road commanded world attention once more in the 21st century, with the building along it of the 10,900-km transcontinental railway connecting Lianyungang, Jiangsu province in the east with Rotterdam, the Netherlands, in the west. It thus reverted to its function of facilitating China’s international trade.

Interest in the Silk Road has intensified worldwide in recent years. In February 2008, senior officials from 19 European and Asian countries, including China, Russia, Iran and Turkey, signed an agreement in Geneva promising more investment in restoring the Silk Road and other time-honored passages of trade between Asia and Europe.

The Routes

The Silk Road in a broad sense contained at least four routes. Zhang Qian and his delegation opened up the most important one during the Western Han Dynasty. It started from Chang’an (today’s Xi’an), headed up the Gansu Hexi Corridor to Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, on to Central and West Asia and eventually Europe.

Rather than a single route, the road comprised several branches. One went across Congling (today’s Pamir Plateau) to Dayuan (today’s Farghana Valley), headed down to Bactria (in today’s Xin-jiang Uygur autonomous region), Sogdiana (in today’s Uzbekistan) and Arsacid, leading to Lixuan in the eastern Roman Empire (today’s Alexandria in Egypt). Another branch traveled through Xuan-du (in today’s Pakistan), Jibin (in today’s Kabul in Afghanistan), Alexandria Prophthasia (today’s Sistan) to Taoke (in the area between today’s Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan) in the southwest. Heading southward from Jibin, a sub-branch reached the Indus river mouth (today’s Karachi in Pakistan). The route then led on to Persia and Rome by sea.

|

|

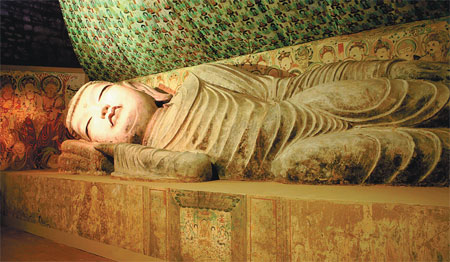

A reproduction of the famed Nirvana Reclining Buddha of Dunhuang, from the Tang Dynasty, can be seen in Turkey's capital. Provided To China Daily

|

In order to avoid passing through the rival Western Xia (1038-1227) monarchy, in the 10th century the government of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) opened up the Qinghai Route. It started from Tianshui in Gansu province and passed through Qinghai and the Western Regions, functioning as an alternative southern route. Until now, most of the Persian silver coins discovered in China have been found in Qinghai province. This shows that the region was of equal importance to the Hexi Corridor in the development of the Silk Road.

The Southwest Silk Road is the second of its kind. Before Zhang Qian and his delegation established the Silk Road mainline, merchants in Southwest China had followed a route from Sichuan capital Chengdu to Yunnan province and on to Burma, India and Pakistan and Central Asia, where they exchanged goods. At that time, cloth and silk produced in Sichuan and Yunnan were in world demand. Merchants transported the products on mules via the Southwest Silk Road to India and Europe.

We Recommend: