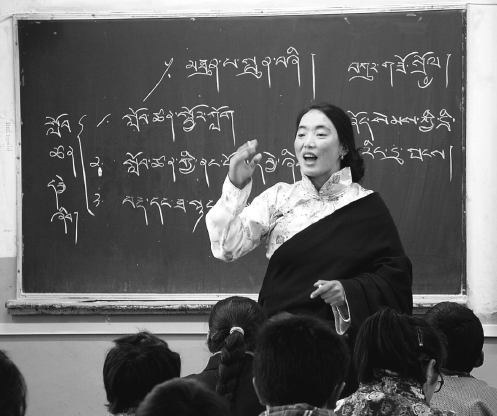

WU TONG/CHINA DAILY

A teacher gives a Tibetan language class at Gannan Tibet autonomous prefecture in Gansu province.

Preserving the Tibetan language is integral to keeping the culture alive, but as new words creep into the vocabulary, many linguists fear for the future. Xinhua reports in Xining, Qinghai province.

Pu Tsering, a good-natured primary school teacher, is very strict when it comes to the Tibetan language.

"We should speak standard Tibetan," the 37-year-old language teacher often tells his students at a boarding school in Yushu, a Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Northwest China's Qinghai province.

"As a Tibetan teacher, I'm responsible for preserving our mother tongue," Pu Tsering says.

When he goes to the bars and cafeterias in town he insists on asking for "maqepu chang" when all his childhood friends say "Yellow River Beer" in Mandarin. He hopes to keep his own Tibetan pure and set an example for his students.

"Many new words-such as iPhone, iPad and Twitter-do not exist in Tibetan," says Yeshi Soiba, a native of Yushu who graduated from the University of Kent in England. "It's very easy to use the English words, so no one has bothered to make up equivalents in Tibetan."

Yeshi Soiba is a program liaison officer with the local government in Yushu.

He is fluent in Tibetan, and switches freely between Mandarin and English, languages he acquired at university. "I majored in environmental protection and community development, and it was extremely difficult for me to find Tibetan-sometimes even Mandarin-equivalents of terminologies."

In fact, the lack of new words is a cause for concern among Tibetan linguists.

"All languages change with time and the same is true of Tibetan," says Genqub Tenzin, who is a Tibetan-Mandarin translator in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province that neighbors the Tibet autonomous region.

"As the Tibet plateau is no longer isolated from the rest of the world, its language is updated with a rapidly expanding vocabulary of borrowed words," he says.

New lexicon

Genqub Tenzin is one of many Tibetan linguists working to preserve the language.

He is head of a government-run Tibetan textbook compilation committee that edits written work for primary and middle schools in Tibet as well as other Tibetan areas in Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu and Yunnan provinces. Translation of borrowed words is an increasingly important job in the committee's editing.

"When we cannot find a Tibetan equivalent, we try to work out new phrases, or paraphrase the idea with existing Tibetan words," he says. "Transliteration is our last choice."

In one of their latest works, a Tibetan-Chinese-English dictionary of new words and terminologies, Genqub Tenzin and his trilingual team submitted more than 13,000 entries, including new Tibetan coinage for computer, mouse, web users and even microblog.

First published in 2006, the dictionary has lagged behind the development of technology and the influx of new words.

"There's a lot more to be done," says Genqub Tenzin. "We have to move faster in updating the Tibetan lexicon. Hopefully, we'll also promote standard Tibetan to replace the different dialects in different parts of Tibet and other Tibetan communities in western China."

Bilingual education

Pu Tsering says he understands youngsters' interest in novelty and their eagerness to catch up with modern life and new technology. "After all, they are living in a world vastly different from the one where their parents and grandparents lived."

When he was a child, Pu Tsering learned to recite long chapters from King Gesar, a classic Tibetan epic. He still remembers vividly the texts from "King of the horse race" and "Saving his wife from hell".

"Such classic pieces are rarely found in children's textbooks nowadays," he says. "Like elsewhere in China, textbooks are more functionally tailored to pass exams."

He often tells his students to speak and read Tibetan as much as possible, fearing the younger generation might one day forget their traditional language and culture in their pursuit of modernity.

The Chinese government encourages bilingual education at schools in Tibet and other ethnic regions. In Tibetan areas, most classes are taught in Tibetan, though Mandarin and English classes are also on the curriculum.

Teachers in Tibetan areas are given on-the-job training to help with their bilingual teaching.

"We have trained more than 35,000 primary and middle school teachers in the province since 2004," says Dong Haifeng, deputy dean of the ethnic teachers' college of Qinghai Normal University.

At least half of these teachers received bilingual training, in Tibetan and Mandarin, he says. The college, which also trains undergraduates to become bilingual teachers at Tibetan schools, instructs most freshman and sophomore classes in Tibetan, says Dong.

"Juniors and seniors are taught in Chinese, but tutorials are given, after class and in Tibetan, at the students' individual requests," he says.

Upon graduation, the students are required to pass Tibetan as well as Chinese language proficiency tests, he says.

The school has obtained more than 40 sets of Tibetan-Chinese bilingual textbooks covering arts as well as science to ensure students are well-grounded in both languages.

Meanwhile, the Chinese central government and Tibet's regional government have invested more than 1 billion yuan ($163 million) since 2008 to boost technological application of the Tibetan language, including the development of Tibetan-language office software and digital dictionaries.

Last year, the first Chinese-Tibetan bilingual smartphone went on the market in Lhasa, capital city of Tibet. The phone was jointly developed by the country's technology firm Huawei, China Telecom's Tibetan branch and the University of Tibet. It allows Chinese and Tibetan input and supports many Tibetan-language applications.

"Tibetan is a unique language, colorful and explicit," says Yeshi Soiba. "For example, there are different names for calves aged from 1 to 7. To know the language will help you understand the Tibetan culture and people."

We recommend: