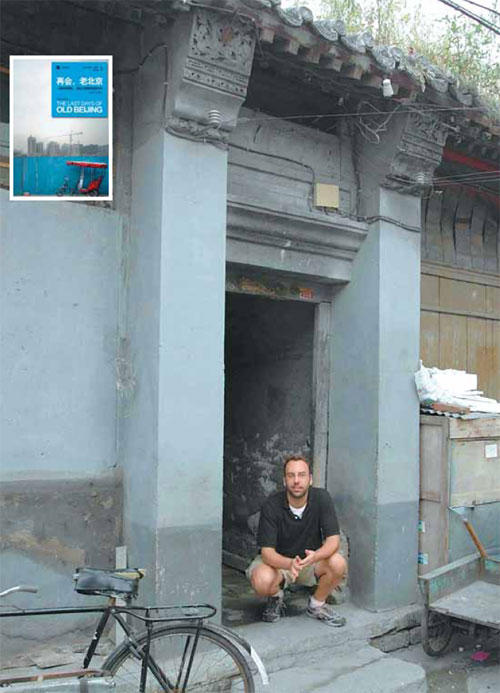

Michael Meyer delves into life in the hutong, a world that is disappearing as the capital urbanizes. Inset: His 2008 book was recently published in Chinese. Below: Meyer and his neighbors. Photos Provided to China Daily

American author's fascination with people in Beijing's traditional courtyard homes inspires passion for an ancient lifestyle, Han Bingbin reports.

One of Michael Meyer's earliest impressions of Beijing was from Marco Polo's description in the 13th century: "The whole interior of the city is laid out in squares like a chessboard with such masterly precision that no description can do justice to it."

For the US author, his journey of discovery started from the heart - and the old parts - of Beijing, which is roughly the size of Manhattan.

As Meyer wrote in a magazine article titled Beijing Forever, "narrow lanes called hutong still stand, lined by gray-walled and single-story courtyard homes whose tiled roofs need weeding".

For centuries the rigid grid of hutong characterized Beijing's culture, he notes, with locals saying turn north, south, east and west instead of left and right. So he's confused enough to find that fewer than one-eighth of Polo's "chessboard" remains.

In 1997, Meyer moved to Beijing after living for two years in Sichuan province, where he worked as a Peace Corps volunteer. Since then, he has watched as many hutong meet the wrecking ball.

Cultural heritage protection subsequently became his focus as a journalist. Seeing that the staunchest hutong protectors are mostly tourists and historians, he realized that the only way to find out whether the hutong deserves protection was to live there.

"I want to see history, but I also want to experience the daily lifestyles," he says.

He spent two years of rustic life in the dull and dilapidated hutong, deprived of elements of modern lifestyle such as a private toilet and bathroom. But the result is illuminating: a thought-provoking book called The Last Days of Old Beijing, offering detailed accounts of lives while revealing the meaning of hutong.

It all happened in Yangmeizhu Xiejie. There Meyer attained a job as an English teacher, a respected role that soon enabled him to become a trusted part of the community.

But it still took almost one year before his neighbors agreed to share their untold life stories with him for the book.

Meyer says when he was "a snobbish journalist", he barely kept any contact with his interviewees after pushing them for quotes he needed for a story. But this time he tried to be friends with people, politely and patiently waiting till they offered to share.

Their stories finally started to emerge, conjuring up a world that Meyer found is not risky and disorderly as imagined by outsiders. Instead, it's a world that's "safe and full of vitality".

In this world, he had to get along with an enthusiastic old widow, his neighbor and landlady who has a personal history perhaps more revealing than the written records of the city.

He was also given a rare "opportunity" by the neighborhood's garbage man to visit a dumping ground.

He once even went to a remote village in Shaanxi province, hoping to catch up with the life of Lao Liu, a noodle-shop owner who returned home after a demolishing plan led him to bankruptcy.

Meyer's 2008 book is now being introduced in a Chinese version - hard to call a "translation" since the words are resuming their original form.

The author's pursuit of purely human-interest stories, critics say, offers a fresh approach to writing city chronicles.

In a recent public dialogue with Meyer, Liu Suli, owner of Beijing's well-known independent Wansheng Bookstore and a veteran observer of China's publishing market, said he has read many Beijing chronicles, none of which, however, is like Meyer's.

"The point of being a foreigner in this situation is not really a different perspective, but the different training he received in writing," Liu says.

"If you don't write well about people, you can hardly reveal the nature of a city."

Liu says the value of Meyer's writing is that, though he obviously has a stance, he doesn't criticize. Instead, he is like a camera, faithfully recording what he saw and heard.

Wang Chunyuan, author of the newly released Beijingers in the Eggshell, crowned Meyer's act as "a pilgrimage" of some sort because he "willingly wormed his way into the texture of the city" and freeze-framed the last moment of Beijing's traditional lifestyle before it changed.

Decades of urbanization will deprive many cities of their basic memories and lifestyles, Wang says, which is a huge "cultural sorrow".

Shabby as it is, Meyer says, the hutong is a place where some lifestyles, such as keeping pigeons, become habitual and can hardly be practiced elsewhere, where outsiders blend into locals and migrants turn into citizens, and where locals build up a solid social network and find themselves a comfortable role.

It's undeniable that the conditions are poor, and that's why many, especially young people, want to move out.

The ideal situation, Meyer says, is let those who want to stay stay and give them sanitation and safety. At any rate, he says, people should have a choice and a say.

Contact the writer at hanbingbin@chinadaily.com.cn.