The reemergence of China as a dominant global actor highlights longstanding ambiguities in U.S. thinking regarding what constitutes national security. People’s Republic of China (PRC) policymakers have emphasized the “peaceful” nature of China’s rise and have generally avoided military or political actions that could be seen by the United States as “threatening.” Nonetheless, the economic, institutional, and cultural battles through which the PRC has advanced its position have both leveraged and contributed to an erosion of the U.S. strategic position globally. The advance of China and the multidimensional strategic challenge that it poses are most effectively characterized by one of the most loosely defined and misunderstood buzzwords in the modern parlance: soft power.

The concept of soft power was introduced in 1990 by Harvard Professor Joseph Nye, who defined it as “a dynamic created by a nation whereby other nations seek to imitate that nation, become closer to that nation, and align its interests accordingly.”1 Although the term is used to refer to a range of concepts, this article analyzes Chinese soft power in terms of the willingness of governments and other actors in the international system to orient themselves and behave in ways that benefit the PRC because they believe doing so to be in their own interests.

Such a definition, by necessity, is incomplete. There are many reasons why other actors may decide that actions beneficial to the PRC are also in their own interests: they may feel an affinity for the Chinese culture and people and the objectives of its government, they may expect to receive economic or political benefits from such actions, or they may even calculate that the costs or risks of “going against” the PRC are simply too great.

Soft power is a compelling concept, yet it operates through vaguely defined mechanisms. In the words of Nye, “in a global information age . . . success depends not only on whose army wins, but on whose story wins.”2 The implications of soft power in the contemporary environment are difficult to evaluate because they involve a complex web of interconnected effects and feedback in which the ultimate results of an action go far beyond the initial stimulus and the ultimate importance of an influence goes far beyond what is initially apparent.

This article examines Chinese soft power in the specific context of Latin America. The United States has long exercised significant influence in the region, while the PRC has historically been relatively absent. Nonetheless, in recent years, China’s economic footprint in Latin America, and its attempts to engage the region politically, culturally, and otherwise, has expanded enormously. Understanding the nature and limits of PRC soft power in Latin America casts light on Chinese soft power in other parts of the world as well.

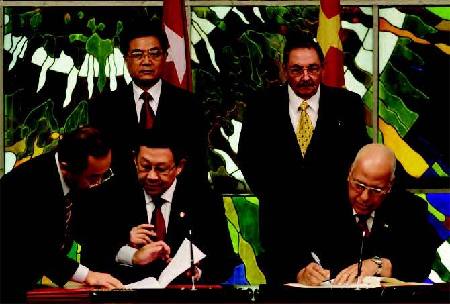

Chinese President Hu Jintao and Cuban President Raul Castro watch signing of treaties in Havana after Hu signed dozens of trade and investment deals with Cuba

The Nature of Chinese Soft Power

In general, the bases of Chinese soft power differ from those of the United States, leading analysts to underestimate that power when they compare the PRC to the United States on those factors that are the sources of U.S. influence, such as the affinity of the world’s youth for American music, media, and lifestyle, the widespread use of the English language in business and technology, or the number of elites who have learned their professions in U.S. institutions.

It is also important to clarify that soft power is based on perceptions and emotion (that is, inferences), and not necessarily on objective reality. Although China’s current trade with and investment position in Latin America are still limited compared to those of the United States,3 its influence in the region is based not so much on the current size of those activities, but rather on hopes or fears in the region of what it could be in the future.

Because perception drives soft power, the nature of the PRC impact on each country in Latin America is shaped by its particular situation, hopes, fears, and prevailing ideology. The “Bolivarian socialist” regime of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela sees China as a powerful ally in its crusade against Western “imperialism,” while countries such as Peru, Chile, and Colombia view the PRC in more traditional terms as an important investor and trading partner within the context of global free market capitalism.

The core of Chinese soft power in Latin America, as in the rest of the world, is the widespread perception that the PRC, because of its sustained high rates of economic growth and technology development, will present tremendous business opportunities in the future, and will be a power to be reckoned with globally. In general, this perception can be divided into seven areas:

■ hopes for future access to Chinese markets

■ hopes for future Chinese investment

■ influence of Chinese entities and infrastructure in Latin America

■ hopes for the PRC to serve as a counterweight to the United States and Western

institutions

■ China as a development model

■ affinity for Chinese culture and work ethic

■ China as “the wave of the future.”

In each of these cases, the soft power of the PRC can be identified as operating through distinct sets of actors: the political leadership of countries, the business community, students and youth, and the general population.

Hopes for Future Access to Chinese Markets. Despite China’s impressive rates of sustained growth, only a small fraction of its population of 1.3 billion is part of the “modern” economy with the resources that allow them to purchase Western goods. Estimates of the size of the Chinese middle class range from 100 million to 150 million people, depending on the income threshold used, although the number continues to expand rapidly.4 While selling to Chinese markets is a difficult and expensive proposition, the sheer number of potential consumers inspires great aspirations among Latin American businesspeople, students, and government officials. The Ecuadorian banana magnate Segundo Wong, for example, reportedly stated that if each Chinese would eat just one Ecuadorian banana per week, Ecuador would be a wealthy country. Similar expressions can be found in many other Latin American countries as well.

In the commodities sector, Latin American exports have expanded dramatically in recent years, including Chilean copper, Brazilian iron, and Venezuelan petroleum. In Argentina, Chinese demand gave rise to an entire new export-oriented soy industry where none previously existed. During the 2009 global recession, Chinese demand for commodities, based in part on a massive Chinese stimulus package oriented toward building infrastructure, was perceived as critical for extractive industries throughout Latin America, as demand from traditional export markets such as the United States and Europe fell off.

Beyond commodities, certain internationally recognized Latin American brands, such as José Cuervo, Café Britt, Bimbo, Modelo, Pollo Campero, and Jamaican Blue Mountain coffee, sell to the new Chinese middle class, which is open to leveraging its new wealth to “sample” the culture and cuisine of the rest of the world. Unfortunately, most products that Latin America has available to export, including light manufactures and traditional products such as coffee and tropical fruits, are relatively uncompetitive in China and subject to multiple formal and informal barriers to entry.

Despite the rift between hopes and reality, the influence of China in this arena can be measured in terms of the multitude of business owners who are willing to invest millions of dollars and countless hours of their time and operate in China at a loss for years, based on the belief that the future of their corporations depends on successfully positioning themselves within the emerging Chinese market.

The hopes of selling products to China have also exerted a powerful impact on political leaders seeking to advance the development of their nations. Chilean presidents Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet, for example, made Sino-Chilean trade relations the cornerstone of Chile’s economic policy, signing the first free-trade pact between the PRC and a Latin American nation in November 2005. Peruvian president Alan Garcia made similar efforts to showcase that nation as a bridge to China when it hosted the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in November 2008. Governments in the region have also invested significant sums of money in the China-related activities of trade promotion organizations such as APEX (Brazil), ProChile, ProComer (Costa Rica), Fundación Exportar (Argentina), and CORPEI (Ecuador), among others, as well as representative offices in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and other Chinese cities, with the objective of helping their nationals to place products in those countries. Latin American leaders, from presidents to mayors, lead delegations to the PRC and fund elaborate pavilions in Chinese culture and trade shows such as the Canton Trade Fair and the Shanghai World Expo in an effort to help their countries’ businesses sell products in the PRC.

Hopes for Future Chinese Investment.

China’s combination of massive sustained trade surpluses and high internal savings rates gives the PRC significant resources that many in Latin America hope will be invested in their countries. Chinese president Hu Jintao helped to generate widespread awareness of the possibility of Chinese investment in the region during his trip to five Latin American countries in 2004, specifically mentioning tens of billions of dollars in possible investment projects. A public controversy over whether his use of the figure $100 billion was actually referring to trade or investment has only called more attention in Latin America to China as a potential source of funds.

Although the expected Chinese investment was initially slow to materialize, today, thanks to China’s growing familiarity with doing business in Latin America, and its enormous financial reserves (including a foreign currency surplus that had reached $2.5 trillion by mid-20105), the PRC has begun to loan, or invest, tens of billions of dollars in the region, including in high-profile deals such as:

■ $28 billion in loans to Venezuela; $16.3 billion commitment to develop the Junin-4 oil block in Venezuela’s Orinoco oil belt

■ $10 billion to Argentina to modernize its rail system; $3.1 billion to purchase the Argentine petroleum company Bridas

■ $1 billion advance payment to Ecuador for petroleum, and another $1.7 billion for a hydroelectric project, with negotiations under way for $3 billion to $5 billion in additional investments

■ more than $4.4 billion in commitments to develop Peruvian mines, including

Toromocho, Rio Blanco, Galleno, and Marcona

■ $5 billion steel plant in the Brazilian port of Açu, and another $3.1 billion to purchase a stake in Brazilian offshore oil blocks from the Norwegian company Statoil; a $10 billion loan to Brazil’s Petrobras for the development of its offshore oil reserves; and $1.7 billion to purchase seven Brazilian power companies.

For Latin America, the timing of the arrival of the Chinese capital magnified its impact, with major deals ramping up in 2009, at a time when many traditional funding sources in the region were frozen because of the global financial crisis. Moreover, as Sergio Gabrielli, president of the Brazilian national oil company Petrobras has commented, China is able to negotiate large deals, integrating government and private sector activities in ways that U.S. investors cannot.