Mummies, and They’re Not Egyptian

Nineteenth and 20th century Western accounts and 16th century Chinese literature is one thing, but for a deeper look into Xinjiang’s long history from the local perspective one can’t go past a visit to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum in Urumqi.

Covering 7,800 square meters and featuring a collection of 50,000 items, the museum is a literal treasure trove. Historical relics include iron tools, bronze wares, pottery, weapons and coins, some of which date back thousands of years.

But unquestionably the highlight of the museum is its collection of mummies, discovered in and around Xinjiang’s Tarim Basin. Numbering 21 in total, the mummies are remarkably well preserved thanks to the basin’s arid climate.

The “Loulan Beauty,” who is estimated to have died as an attractive young woman around 4,00 years ago, is one of the oldest mummies on display. While her skin is tinged an unnatural reddish brown, the rest of her remains are eerily intact. Her long, matted brown hair, tall nose and intact finger and toenails make for evocative – if a little gruesome – viewing.

The “Loulan Beauty” is also testament to Xinjiang’s history at the crossroads of Eurasia. Studies of her mummified remains reveal she was Europoid, and hence the genetic kin of modern Europeans. This also suggests she spoke an Indo-European language, most likely Tocharian, a scarcely documented, nowextinct cousin of Armenian, Hindi, Russian, English and all other languages in our broad language family.

The Birth of Culture and Its Legacy

In the first millennium BC, the nomadic ancestors of the modern Uygur people settled in the oases around the Tarim Basin, displacing and absorbing non-Turkic speakers such as the Loulan Beauty and her Tocharian brethren. As an agrarian society developed, a vibrant culture took root that absorbed influences from China’s Central Plains, India, Tibet, Iran, and even Greece and the Roman Empire. In the 9th century Islam found its way to Xinjiang; Islamic influence and indigenous culture inexorably intertwined to form a rich heritage that continues to this day.

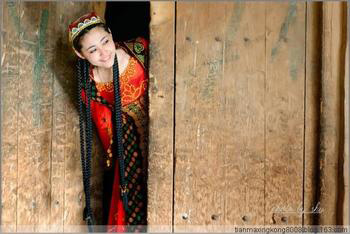

One particularly beautiful facet of Xinjiang’s cultural heritage is music and performance. A cliché often heard in East China with regards to this heritage is that “Uygur love to sing and dance.” It’s easy to dismiss such a comment as a kind of “reverse orientalism” – exoticising the other “other” – but on actually visiting Xinjiang, it turns out that, for once, the cliché seems to hold true.

Most Uygur social gatherings are held to the accompaniment of live music. Weddings ceremonies, or Toi, are the liveliest of occasions, resembling more a carnival than the dour “exchange of vows” of the Western tradition.

True to the diverse influences on local culture in general, Uygur music is a quixotic cocktail of Arabic, Persian, Chinese, Russian, Mongolian and native elements.

In any one musical performance, dozens of musical instruments may be used, chief among which are usually a large tambourine- like drum and the dutar, a long-necked two-stringed lute. Dutar virtuosos can tackle music written for the fourstringed violin and come away smiling.

Standing paramount in the Uygur musical tradition is the Muqam. Developed over one and a half millennia, the Muqam finds its genesis in the Arabic ‘Maqam’ melody system. Nowadays the Muqam has been thoroughly indigenized and is highly regionalized, though all variants are based on the “Twelve Muqam,” an epic narrative whose performance includes classical and folkloric song, music and dance.

“The Uygur Muqam Art of Xinjiang, China” has been designated by UNESCO as part of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Domestically, the Muqam and 13 other intangible cultural heritages in Xinjiang were included in the first batch of China’s officially recognized intangible cultural heritages in 2006. This should ensure Muqam traditions and performance skills are passed down to younger generations.