CHINA DAILY

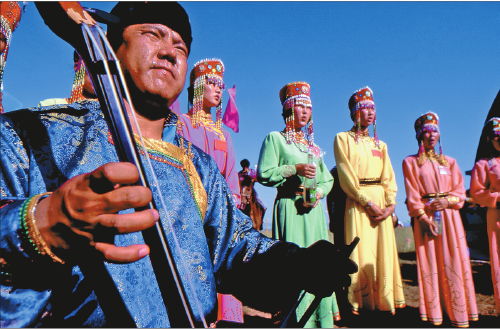

Singing has been an indelible part of life for Mongolian people who always have music on their lips and in their hearts.

ZHAO TINGTING/XINHUA

Mongolian people have a rich cultural heritage including music and dance, but some of these skills are disappearing.

WANG KAIHAO/CHINA DAILY

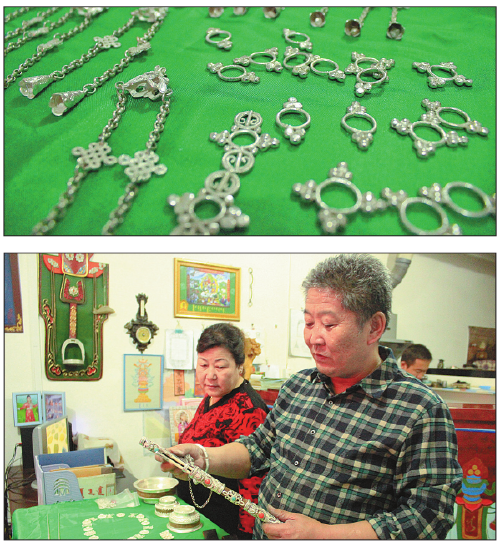

Battogoo runs a workshop to revive the traditional silverware craftsmanship in Urad Middle Banner, Inner Mongolia.

CHINA DAILY

It's a beautiful song known at every campfire around which Mongolians gather. Wang Kaihao looks at the stories behind the Urad ballads, and also the threatened crafts in Bayannur, Inner Mongolia, that are slowly disappearing.

For Mongolians everywhere, the nostalgic lyrics of the Swan Goose ballad is most often sung at the dinner table when it is time to propose a toast.

"When the goblet is empty, make it full again. No one returns home tonight until everyone is happily drunk …"-the words best reflect the spirit behind Mongolian hospitality and outlook.

For members of the tribe of Urad, however, the lightheartedness is tinged with the bittersweet, especially in the western city of Bayannur in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, where the song originated more than 200 years ago.

Narantogos, 68, is a veteran ballad singer living in Urad Middle Banner, a county-level administrative district along the Sino-Mongolian border. Though she moved into town more than 10 years ago, the memories of her home on the great grasslands still haunt her.

"The Urad ballad is rooted in our daily life when we herd sheep," she says. "The lyrics are often impromptu, and flow from our minds. We sing for the grassland and what we see in nature."

As early as the 1940s, Narantogos' mother was already occasionally performing in an arts troupe. She herself made her debut on the professional stage in 1965 in Hohhot, capital of the autonomous region.

She jokingly notes that among her vast family, she is the only one to have inherited her mother's vocal talents.

According to Liu Bin, curator of the Urad Middle Banner Museum, Tibetan Buddhism was once popular among Urad tribe members. About 80 percent of the ballads still being sung today were composed by the lamas in the 17th and 18th century.

Urad ballads were included as a national intangible cultural heritage in 2011 as an extension of the Mongolian ballad.

Narantogos is officially one of three cultural inheritors of the Urad ballads, but she did not seem aware of this until we interviewed her.

Compared to the music of other Mongolian tribes, Urad melodies are more soothing, exemplified by the ballad of the Swan Goose.

"I guess that's probably because we ride camels more, while Mongolians in the east are always galloping on horses," she says with a smile.

In 2008, the banner's cultural bureau helped publish books which recorded traditional ballad scores and lyrics.

Vocalist Sarna is from the bureau, and she is also Narantogos' niece. She admits that the collections depended more on the decision-makers' subjective interests rather than an objective curating.

A ballad competition was held to encourage the effort to preserve the ballads, but Sarna and Narantogos feel this is not enough.

Narantagos is working hard to preserve this heritage in her personal capacity, and she has taken in more than 10 apprentices without charging any money.

She feels that it is urgent, and that she has to pass it on so more young people can learn this genre of music. Already, age is making her voice raspy.

This urgency also applies to other Urad intangible cultural heritage.

Urad means "artisan" in Mongolian, and the tribe has been known for its skilled craftsmen since the days of Genghis Khan. However, this glory is fading fast.

Battogoo, 50, runs a workshop making silverware. Although he recalls seeing silverware everywhere when he was a child, he realized that it was disappearing from the market.

He became determined to revive the craft around 2006, when the government sent out a call to revitalize the industry.

Battogoo had learned silver-craft when he was younger, and it was easy for him to pick it up again.

He knows things will never be the same. Part of the old processes has been replaced by modern tools. While he appreciated the convenience, he also regretted the passing of traditional handwork.

He has two apprentices, and together they run the three silverware workshops in the banner seat. Museum curator Liu estimates that the total number of silversmiths in the banner to be only around 10.

Urad silverware was listed as Inner Mongolia's intangible cultural heritage in 2011.

"There's no need to compare our Urad silverware with those in the southern provinces. They are all recordings of local folklores from their respective cultures. Urad silverware represents the nomadic civilization, and is closer to localized aesthetic standards," Liu says.

Battogoo does not display his work in showcases. Instead he only makes to order. A whole set of silver wedding hair accessories may weigh as much as 1.8kg and cost about 40,000 yuan ($6,600). It will also take the full commitment of two silversmiths, who may use up to two months to create the jewelry.

Curator Liu says his museum has opened up a 700-square-meter hall to exhibit Urad intangible cultural heritage items, but confesses that it did not attract enough attention locally.

"Nearly 20,000 people visited the hall last year, but the vast majority were tourists. If we are not able to get the local people interested in the heritage, we will find it more difficult to protect it."

To encourage better appreciation and understanding, Liu says, the banner will establish an intangible cultural heritage protection association in the near future to offer all item inheritors a better platform to display their talents.

This is a common problem for those who try to protect Bayannur cultural heritage.

"Many people have the wrong idea that intangible cultural heritage means songs and dances," says Liu Fei, head of Bayannur municipal office in charge of cultural protection. It is a lot more, he adds.

"Protection of these items needs much behind-the-scenes work, including compiling historic archives, and establishing a database. We need money to carry this out."

Bayannur gets 200,000 yuan every year from the local government for intangible cultural heritage-related work, but Liu Fei says it is not enough.

"Everyone here works for the love of the culture. We struggle to apply for more financial support, but that's all we can do," Liu Fei says.

More visible items like the Urad ballads and silver-craft are being revitalized, but the lesser-known glass and brick paintings are inevitably disappearing.

"The ancient Urad tribe never lacks for cultural treasures, but without professional help in collating relevant data needed for the bid for intangible cultural heritage status, they will soon be lost."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn.

We recommend: