The day before opening night Tan Dun attended “A Conversation with Tan Dun at the Met” and shared his life experiences and thoughts on creating Kunqu Opera in modern times.

At the event he recalled his first brush with the ancient art form when he was studying composition at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. “One day I met with Yang Chunxia, who starred in Dujuan Mountain (one of the revolutionary Peking Opera plays officially sanctioned during the “cultural revolution”), and learnt she had actually started her career as a Kunqu Opera singer. She performed an aria from Peony Pavilion for me, and I was mesmerized. I immediately fell in love with Kunqu.”

Tan also explained his decision to set the performance in a real garden, saying that it came to him in an epiphany when he was in a traditional Chinese courtyard. As he was enjoying the sounds of birds and insects amid the babble of flowing water the peace was suddenly disrupted by a gust of wind. When it passed the music of nature returned, and he thought to himself: “Oh my, that’s Kunqu. This is why in old times the opera was staged in gardens instead of theaters.”

It was popular practice among the upper echelons of the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644) to host Kunqu performance in their private gardens, and Tan Dun sees good reason for that. “A garden, with its flora and fauna, is a medium of communication between its occupants, heaven and earth.”

Intent on offering their audience a perfect recreation of the ambience of the archetypal Chinese garden, Tan’s production team imported huge numbers of props into the U.S., including 24 purebred Chinese goldfish and recordings of birds singing in the garden on which the Astor Court was modeled.

“This retrofit of Peony Pavilion is what I envisioned in my mind, one of unsophisticated beauty as it was back in the Ming Dynasty,” Tan Dun told reporters after the performance.

Zhang Jun, who brings the play’s hero to life, said the distinctiveness of Tan’s Peony Pavilion lies in this unconventional setting. “Every garden is unique. Before performing in a new location, we would spend days studying it and modify our performance to make it fit into the surroundings. This way every group of performances at a different venue is one of a kind.”

Zhang Ran, who plays the ghost lover, confessed that she found it more of a challenge to perform in the Astor Court than in the Kezhi Garden in Zhujiajiao, an ancient town in Shanghai’s suburbs, where the play had previously been staged for two years. “The performance space is much smaller at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and it’s closer to the auditorium. Every nuance of the players’ body movements and facial expressions was discernible to the audience.”

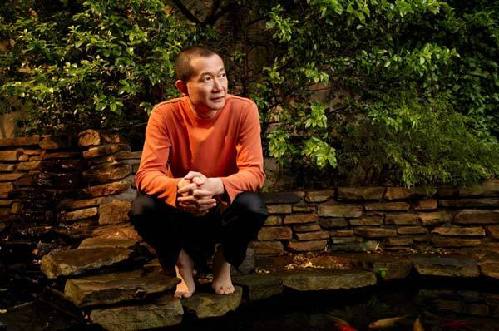

Composer Tan Dun's love for traditional Chinese culture is revealed in his work, most recently the garden-based version of The Peony Pavilion, a classic of Kunqu opera from the 16th century.

Cultural Barrier?

Tan Dun’s version of Peony Pavilion has only four acts, compared with the original 55. It was first staged in a private mansion built at the beginning of the 20th century in Shanghai’s Zhujiajiao Town. It was there that Maxwell K. Hearn, curator of the Met’s Asian Art Department, watched this version and proposed to Tan Dun that they bring it to the Metropolitan Museum.

There could be no better site in the U.S. to present this Kunqu classic than the Astor Court. Conceived of by the museum’s trustee Brook Astor, who spent a period of her childhood in Beijing, the installation was created and assembled in 1981 by expert craftsmen from China using traditional methods, materials and hand tools. Its design was masterminded by Professor Chen Congzhou, an architectural historian from Shanghai’s Tongji University. The project was the first collaboration in gardening art between the U.S. and the PRC.