Each of China’s ethnic minorities has a discrete building style that immortalizes its culture and anchors its esthetics. That of the Dong ethnic minority, who live mainly in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region and Guizhou and Hunan provinces, is the windand- rain bridge – a roofed, sometimes walled multi-tiered structure of curved eaves and pavilions. It is distinct from other Chinese bridges by virtue of the defining elements of pagoda, pavilion and gate tower combined through a conventional configuration. These auxiliaries are both ornamental and functional as they provide shelter during south China’s frequent heavy rains and strong winds.

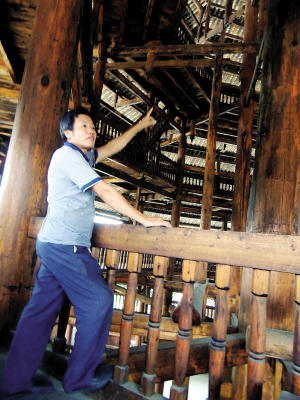

Yang Siyu masterminded construction of the wind-and-rain bridges and drum tower in Linxi Township, Sanjiang Dong autonomous county in northern Guangxi. Born in 1955 to a family of carpenters and bridge builders, Yang began learning his trade from his father at age 13. He has over the past four decades designed six wind-and-rain bridges, more than 100 stilted homes, eight drum towers (including one of 27 storeys) and 20- odd pavilions, as well as 2,680 models of bridges and drum towers. In 2007 Yang was nominated as an inheritor of the intangible heritage of traditional Dong wooden-structure architectures.

For Yang Siyu, bridge building is both a family business and obligation.

Intangible Plans

The components of such traditional Dong wooden structures as bridges, drum towers, drama stages and waterwheels fit together through tenons and mortises rather than nails or screws. Despite the precision this type of design demands, the builder embarks on each project guided solely by his mentally conceived plan. Nothing is committed to paper. Dong architects also have the amazing ability to calculate complex mathematical computations in their head, the results of which they jot down on a bamboo pole – their main measuring tool – in an esoteric script.

However obsolete it might seem to the architectural establishment, this centuriesold practice is highly efficient. When, back in 1983, the wooden Chengyang Wind-and-Rain Bridge, built in 1916 and main landmark of Sanjiang county, collapsed under heavy rain, a team of college-trained architects was called in to restore it. In the dismantling process each piece was coded, but reassembling the bridge’s thousands of variously sized parts was agonizingly slow because the team had no guide as to their proper location.